WASHINGTON, D.C. -- In June 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published an article about a mysterious infection that had overcome five young, previously healthy gay men -- all of whom would be dead soon after publication. Since this first report, more than 700,000 Americans with the disease have died; it would come to be identified as acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

Information about the disease was scarce in the earliest days of the soon-to-be national health crisis, and so too was a concerted response from the government to combat its outbreak. In 1982, a journalist asked then-President Ronald Reagan's press secretary if the president was tracking the spread of the disease, which by that point numbered 600 reported cases. The press secretary responded to the reporter, "I don't have it, do you?" The press pool laughed as the secretary admitted, "I don't know anything about it."

But Americans themselves were learning about the virus, as details of the disease began to make it to the front page of national newspapers. By 1983, as reports of AIDS cases climbed to 1,450, more than three in four Americans had heard of or read about AIDS, according to Gallup's first question on the topic. Of those who were familiar with the disease, 43% believed it would reach epidemic proportions, and they were more pessimistic (45%) than optimistic (33%) about whether a cure would soon be found.

Americans' Attitudes on People With AIDS

AIDS predominantly affected men who had sex with men and, as a result, severely hindered the U.S. gay rights movement, which was still in its infancy. Among Americans who reported knowing a gay person, more than one in five (21%) said they had become less comfortable around that person since learning about AIDS.

In 1985, the vast majority of Americans (80%) said it was "probably true" that most people with AIDS were homosexual men. More than a quarter of Americans (28%) reported that they or someone they knew had avoided places where homosexuals might be present as a precaution to avoid contracting AIDS -- and this number grew to 44% by 1986.

As the spread of AIDS continued, ���۴�ýfound some Americans expressing judgmental views about those who had contracted the disease. In two separate polls in 1987, roughly half of Americans agreed that it was people's own fault if they got AIDS (51%) and that most people with AIDS had only themselves to blame (46%). Between 43% and 44% of Americans in 1987 and 1988 believed that AIDS might be God's punishment for immoral sexual behavior.

Still, a solid majority (78%) agreed that people with AIDS should be treated with compassion. But most Americans (60%) also agreed that people with AIDS should be made to carry a card noting they had the virus, and one in three (33%) agreed that employers should be allowed to fire employees who had AIDS. Twenty-one percent of Americans said people with AIDS should be isolated from the rest of society.

Perceptions of AIDS as the Most Urgent U.S. Health Problem

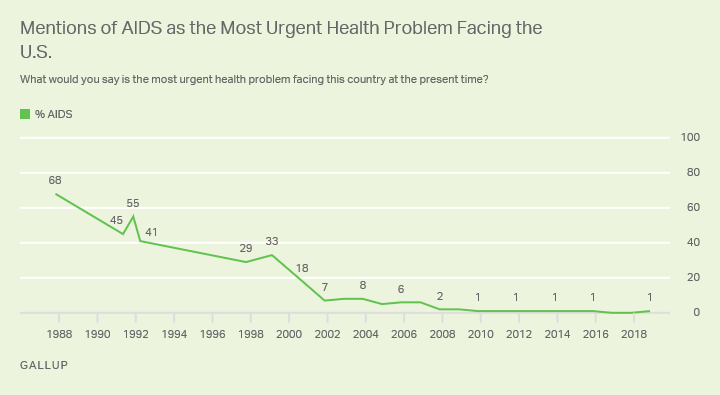

In 1987, ���۴�ýasked an open-ended question about what Americans saw as the most urgent health problem facing the U.S. More than two-thirds of Americans said AIDS, and mentions of the disease topped that list until 2000.

Diagnoses of AIDS and AIDS-related deaths peaked in the early 1990s as scientific understanding of the disease advanced, including the advent of new medications that allowed people who had contracted HIV to live normal lives. In the decades since, Americans' mentions of AIDS as the top U.S. health problem have subsided, and since 2009, no more than 1% of Americans have mentioned AIDS in any of Gallup's polls that have asked the question.

AIDS and HIV are still problems in the U.S., though not to the degree they were during their peak in the 1980s and '90s. The diminished percentages of Americans naming AIDS as the country's greatest health problem reflect the advancements of treatments, which mean that infection with HIV is no longer a death sentence for people.

Read more from the ���۴�ýVault.