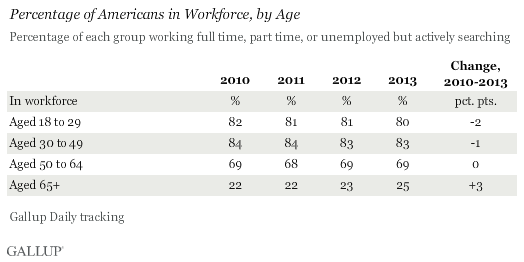

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- As the U.S. economy continues its sluggish recovery from the recession and global economic crisis, more seniors and fewer young adults are in the workforce now compared with 2010. There has been a three-point increase since 2010 in the percentage of Americans aged 65 and older who are in the workforce -- employed full time through an employer, self-employed, working part time, or unemployed but actively searching for work. At the same time, there has been a two-point decrease in the percentage of Americans aged 18 to 29 who are in the workforce.

These results are based on more than 350,000 interviews per year with U.S. adults aged 18 and older. Examining the changing composition of the workforce population since 2010 offers a glimpse into how the labor market has changed as the nation recovers from the 2008-2009 economic recession.

The recession contributed to significant household wealth reductions that Americans are still trying to recoup. Older Americans' desire to replenish their retirement savings may partly explain the three-point increase in the percentage of seniors in the workforce, as more postpone retirement or former retirees re-enter it. In addition, Gallup's employment data show that 12% of those 65 and older are employed full time for an employer or are self-employed full time in 2013 versus 9% in 2010, suggesting that older Americans may be keeping their full-time jobs.

For young adults, joblessness during the recession may have accelerated the trend of living at home with their parents, softening the effects of not having a paycheck. It is also possible that more young adults decided to continue their education in a challenging labor market. A Heritage Foundation study using U.S. Census Bureau data showed a 4.5% increase between 2007 and 2012 in the percentage of 16- to 24-year-olds who remained out of the workforce due to school.

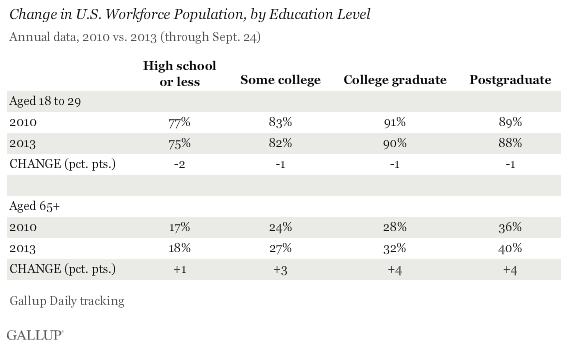

Younger, Less Educated Americans Experience Drop in Workforce Participation

Among Americans aged 18 to 29, the biggest change in workforce participation between 2010 and 2013 is a two-point decrease in the percentage of those with a high school education or less. This may be explained by the inability of some in this group to find work or by their simply seeking more schooling. For 18- to 29-year-olds with some form of higher education, the decreases in employment were more modest.

Those aged 65 and older experienced workforce increases among all levels of educational attainment. This includes four-point increases among those with undergraduate degrees and those with postgraduate education. Workforce participation among seniors who have a high school education or less remained relatively stable, at 18% in 2013 versus 17% in 2010.

Bottom Line

There are more seniors and fewer 18- to 29-year-olds in the workforce now compared with 2010. The sluggish recovery from the Great Recession may explain some of these changes in workforce composition.

Americans' biggest financial concern is funding their retirement, with 61% worried about having enough money for that. This worry has been exacerbated by the recession's aftermath, which has perhaps caused more seniors and baby boomers near retirement age to remain in the workforce and until they have replenished their nest eggs. However, some of these seniors are likely remaining in or even entering the workforce out of personal choice, not necessity. A that half of U.S. adult employees earning at least $75,000 say they will continue working after retirement by choice, while pluralities of lower-income workers intend to remain in the workforce more out of necessity.

Conditions within the labor market have not improved as quickly as policymakers and economists have hoped, with Bureau of Labor Statistics job reports falling short of expectations. Slower job creation and fewer vacancies due to older generations' postponing retirement have contributed to a tough environment for young job seekers, 20% of whom are now out of the workforce.

With the recent tied to uncertainty about the government shutdown and debt ceiling talks, a renewed sense of optimism in job markets and financial markets is unlikely in the near term. More young adults may drop out of the workforce if they struggle to find quality employment or seek to improve their marketability through higher education. It is also possible that more seniors will participate in the workforce if baby boomers for economic reasons postpone their retirement or re-enter the workforce.

Survey Methods

Results for this 优蜜传媒poll are based on telephone interviews conducted Jan. 1, 2010-Sept. 24, 2013, on the 优蜜传媒Daily tracking survey, with a random sample of 264,670 adults, which includes 37,407 aged 18 to 29 and 77,108 aged 65 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is 卤1 percentage point.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by region. Landline and cell telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the March 2012 Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the July-December 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the 2010 census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more details on Gallup's polling methodology, visit .