What has life been like for people in Myanmar in the year since the military coup? Michael Sullivan, who reports from Southeast Asia for NPR, joins the podcast to discuss press freedom, economic pain, struggles to afford food and the record numbers of people who want to flee the country.

Below is a full transcript of the conversation, including time stamps. Full audio is posted above.

Mohamed Younis 00:07

For Gallup, I'm Mohamed Younis, and this is The ���۴�ýPodcast. This week, we look across the globe to Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, and check in on what life has been like for its citizens one year after a coup d'état that derailed an already challenged democracy. Michael Sullivan reports from Southeast Asia for NPR. Michael, it's great to have you on the show.

Michael Sullivan 00:27

Nice being here.

Mohamed Younis 00:28

Can you quickly remind us, what happened in Myanmar about a year ago? How did this coup happen? And is it new for Myanmar to have a coup d'état?

Michael Sullivan 00:36

Not new at all to have a coup. This one happened … this was kind of a surprise, actually. But in retrospect, it wasn't that unexpected by some who really understand the place. I mean, when Aung San Suu Kyi's party won the last democratic election, it was a shock to the military. The military really thought they were going to do well, the military-backed party was going to do well, and it didn't. And suddenly the military commando, the Tatmadaw commander, Min Aung Hlaing, he, he wanted to be president, and when he saw that that avenue to being a president was shut off, he said right then, "I'm going to do what I need to do to take power now and to sort things out."

Michael Sullivan 01:20

That's basically what happened. It shocked a lot of people, but in retrospect, it should not have because the military is very opportunistic and they've been on the sidelines for the last 10 years or so. But they haven't been out of the game at all. They've just been letting other people do things, and they came back with a vengeance. That's what happened on Feb. 1. There's been, I mean, not so much now, but at one point there was talk of things sort of spinning into civil fighting, civil war. What's the climate there now? Is that still a possibility? Is there a peaceful way out of this current fact pattern?

Michael Sullivan 01:54

Yeah, I think we're past that now. I mean, I don't think this is a civil war anymore, because you have a military that has about 400,000 people and then you have the populace, and it's basically the military and the people who support the military who are former military or people who are used to thinking the way the military has taught them to think for the last 70 years, and then you have the other 40 million people, or 50 million people probably is more accurate. And that's what this is right now. And it's devolved and it's not going to get any better until the two sides actually decide they want to sit down and try to negotiate a settlement. But neither side at this point is even remotely willing to do that. This is all or nothing. There's no one in the middle anymore, Mohamed. There is just "us" and there is "them" from both sides. There is no middle ground.

Mohamed Younis 02:49

I want to ask you, Michael … I'm, so I'm originally from Egypt, a place that's also not unknown for military coup d'états. One thing that fascinates me in these situations is the narrative a military provides for why, you know, this had to happen. What is it exactly that the military was claiming to be saving as they came in and sort of instituted this coup d'état?

Michael Sullivan 03:11

They just basically claimed that Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy stole the election through the ballot box. And of course, there is absolutely no evidence this actually happened, but they had to have a pretext for this happening. And as you say, Mohamed, you're familiar with this. They have to have a pretext. And that was their pretext. And then they slapped all these charges against her and against many, many, many senior members of her party to try to make sure that both Aung San Suu Kyi and her party were basically removed from electoral politics in Myanmar for the foreseeable future, if not forever.

Mohamed Younis 03:52

In addition to the security issues, the economy has also really been in shambles there, both because of the coup, but also because of the pandemic. In our data, Michael, we saw people's economic outlooks take a hit during the first year of the pandemic. But they were really bad in 2021. At the end of the year, seven in 10 respondents said their economy was getting worse and most people actually said they're struggling to afford food. Have you seen this in your reporting? What is the economic hurt like right now?

Michael Sullivan 04:23

It's really, really bad, and, you know, this is a "chicken or egg" question: What was it the coup that, you know, precipitated this, or was it the pandemic? I mean, I would argue that it was the coup first and then the pandemic just exacerbated what was happening after the coup … when the civil disobedience movement started, when people refused to go to work, they refused to have anything to do with the military. And that in turn made everyday life basically very difficult. And that's just been made worse over the last 12 months now by the military's extremely heavy-handed attempt to put down this rebellion at this point. You can call it the Spring Revolution, as the protesters like to call it.

Michael Sullivan 05:11

And it's terrible right now because the military has only one goal right now, and that is to make sure that they remain in power. And other things like the economy, like healthcare, like the pandemic, all of these things are distant, distant second, third, fourth or fifth to them. They need to stay in charge, they will do whatever they need to do to make sure that happens, and they don't really care about what's happening next. The pandemic has been really bad for Myanmar because it's a very bad situation for them in general because they have a very rudimentary healthcare system there. So when the pandemic hit, I mean, they have no way to really deal with it, and then you layer on this rebellion on top of that. And it's, it's frightening. So yeah, a lot of people are hungry now, and from what I've been hearing from people there, it's only going to get worse because this thing is not going to get any better, anytime soon.

Mohamed Younis 06:11

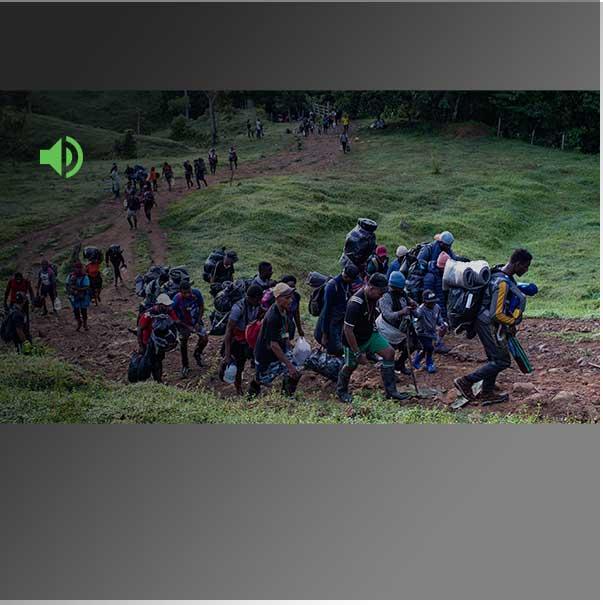

And it seems like citizens really know that intimately more than anybody because another thing that we've seen in our data -- and maybe not surprising given everything you just said -- is we're seeing record numbers of people in Myanmar wanting to flee the country or leave permanently. The percentage actually quadrupled from 6% in 2018 to 24% in 2021. Before that, it had never been out of the low single digits. What does this say to you about Myanmar's neighbors? I want to ask you about the whole Rohingya situation later. But in terms of people just fleeing this current crisis, is that something you're seeing more of? Is that something that surprises you?

Michael Sullivan 06:52

It's not something that surprises me at all. But I also have to say that those single-digit numbers that you're referring to, I don't actually necessarily buy those. I think after 2010, 2011, when there was an opening, people thought things were really going to get better. They were much more optimistic. So that's probably what those polls are based on. They had some optimism that things were going to get better, that the military was going to just sort of recede as it does elsewhere in, in Southeast Asia sometimes. And they were kind of shocked when this thing happened last February, and I think now they're much, much more desperate and they're probably much more willing to say now what they weren't willing to say before, which was they thought they never really had a future in one of the Southeast Asia's poorest countries to begin with.

Michael Sullivan 07:46

And that's why you see millions of Myanmar citizens go to neighboring Thailand, where I live, or Laos or somewhere else to trying to get jobs because there isn't a lot there. There hasn't been for the last 40, 50 years under the military, and they didn't see a life happening for them. So, so they left and they sent remittance money back home. Now, all that's thrown up in the air because everything's … all bets are off right now because, I mean, it's very hard getting remittance money back to Myanmar right now because of the coup and the way the military is controlling the banks and everything else. So, oh, things are getting bad, not only for the people in Myanmar, but for the people here in the diaspora trying to send money back to Myanmar. It's not, it's not working for anyone at this point except maybe the military, but the jury's still out on that too.

Mohamed Younis 08:40

And you mentioned this kind of moment of positivity or optimism that came earlier in, in Myanmar's history before this coup. We see that in our data so dramatically, Michael, like 90% of people at one point were highly satisfied with the freedom to choose what they do with their life. Press freedom was really high. People felt that they had access to, you know, free and fair press. All those numbers have really came crumbling down, as you would imagine, pretty dramatically since the coup. I want to ask you about press freedom. What's the environment there like now, and how dramatically different is it than a few years ago before this happened?

Michael Sullivan 09:20

As you might imagine, it's a lot worse now. There is no press freedom now. There was a great deal of press freedom relatively after 2010, 2011. But don't forget, and this is going down the, you know, another rabbit hole, but don't forget that after the NLD first took power -- or nominally took power, depending on your point of view -- I mean, yes, there was a lot more press freedom. People were a lot happier. But then you remember what happened to the two Reuters reporters who had a very good story on what happened to the Rohingya that was irrefutable and they were thrown in jail. I mean, and this is under Aung San Suu Kyi's allegedly democratic, or more democratic, government.

Michael Sullivan 10:05

So press freedom in Myanmar is a slippery slope. Did it get a lot better after 2010, 2011? Certainly. Was it perfect or even near perfect? No, not at all, as those Reuters journalists would attest. But is it much, much worse now? Yes, there is no press freedom. They're going after … the military is going after the media with a vengeance right now. They don't want any independent reporting coming out. They want to try to control the narrative. But of course that's impossible now with the internet.

Mohamed Younis 10:40

You perfectly teed me up, Michael, for my last question. It has fascinated me how Aung San Suu Kyi was really heralded as a hero, both by the Obama administration, by the global community … really seen as a champion of democracy in our times, in the modern times. And then the situation with the Rohingya unfolded, and the reaction to that, the democratically elected government's reaction to that, as you mentioned, really surprised a lot of people because it didn't necessarily meet up with the expectations that had been created about the kind of leader Aung San Suu Kyi is.

Mohamed Younis 11:15

I have two questions. One is, whatever happened to the Rohingya? Where is that issue at right now? Because it doesn't seem like anyone is focused on it anymore. And secondly, how flawed was the democracy that existed before this coup? One thing that drives me nuts is this notion of "A coup has happened -- we need to go back to freedom and democracy." As though it's like we're going back to utopia. But it's really hard to accept that when under a democracy, there was basically, depending on how you look at it, ethnic cleansing or genocide unfolding and a coverup by that democratically elected government that led to even reporters being arrested, as you mentioned. So just update us on the Rohingya and how much of a democracy was there before this coup.

Michael Sullivan 11:58

It wasn't as great as people like to think it was. And to answer your first question about the Rohingya, I mean, most of them still sadly are stuck in camps in Bangladesh. I mean, close to a million. No, more than a million now, probably, if you take in the first two waves that happened before 2017. Yeah, there's more than a million. So they're there, they're stuck, and then the Rohingya and the diaspora, I mean, in Malaysia and Indonesia, other places, they're there too. They fled for a reason, and that reason was they were discriminated against. And then the democratic government that you referred to, and I know you said it skeptically, remember that Aung San Suu Kyi went to the Hague to defend the military not that long ago.

Michael Sullivan 12:45

So what does that say about how the majority Bamarn community thinks of minorities in the country in general, and how does that inform how they think right now about what's happening in the country? I mean, the military right now thinks it's "us" against "them," and "us" really means the majority Burmese and "them" is everyone else. What the military absolutely refuses to recognize right now is that there is no difference between "us" and "them" anymore because the majority of the people who have, you know, actually accepted what they've been saying for 20 or 30 or 40 or 50 years, it doesn't really matter, those people aren't buying that anymore because they're just sick and tired of their country not going anywhere, and they've lost their majority and they don't get it yet because no one ever wants to tell the emperor he has no clothes. But that's where we're at right now.

Michael Sullivan 13:49

So for the next three or four months, I think, while, while we see what happens in the dry season, I think the next three or four months will be pivotal in terms of what's going to happen in Myanmar in, in the short term, by the short term. I mean, maybe the next year or so, I mean, we'll know, we'll have a pretty good idea in the next three or four months if the Myanmar military can actually put this thing down or if they're past their "sell by" date.

Mohamed Younis 14:15

On that note, Michael Sullivan, revered Southeast Asia correspondent reporting for NPR and many others … Michael, it's so great to have you here.

Michael Sullivan 14:24

Very nice being here. I enjoyed it.

Mohamed Younis 14:25

That's our show. Thank you for tuning in. To subscribe and stay up to date with our latest conversations, just search for "The ���۴�ýPodcast" wherever you podcast. And for more key findings from ���۴�ýNews, go to news.gallup.com or follow us on Twitter @gallupnews. If you have suggestions for the show, email podcast@gallup.com. The ���۴�ýPodcast is directed by Curtis Grubb and produced by Justin McCarthy. I'm Mohamed Younis, and this is Gallup: reporting on the will of the people since the 1930s.