On July 11, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac -- so-called government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that are stockholder owned but government backed -- lost about half their share values in a 24-hour period. U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke rushed to assure Congress and investors that both companies were in good shape and that investors should relax. Both companies were, in fact, able to continue borrowing money to fund their day-to-day operations, and talk of conservatorship eased. On July 27, President Bush signed new federal housing legislation that, among other things, provided unlimited federal backing through 2009 for these two GSEs that operate at the heart of the U.S. housing system.

|

Not surprisingly, given the Bear Stearns bailout, the Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac crisis, and the huge losses reported by many of the nation's largest banking institutions, U.S. consumers' doubts about banks have grown considerably in 2008. In fact, consumer confidence in the banking industry was near an all-time low in June, when a ���۴�ýPoll showed that only 32% of the public expressed "a great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in banks (the lowest point was 30% in October 1991).

Still, the reality is that depositors can have full confidence that their savings are safe and secure in their banks due to the existence of the FDIC and federal deposit insurance; no FDIC-insured customer has ever lost money in a U.S. bank. At the same time, however, bank management needs to continually have in mind that bank customers are more nervous now than they have been at any time since 1991 -- and they need to manage accordingly. (See graphic "Confidence in Banking" and "Confidence in U.S. Banks Down Sharply" in the "See Also" area on this page.)

|

For better and worse

It won't always be this bad for banks. "It will get better -- it just takes time for things to right themselves," says Dennis Jacobe, Gallup's chief economist. "The banking industry and the investment banking business became overleveraged and over risk-exposed during recent years, and the only cure is deleveraging and risk aversion. That takes time, portfolio adjustments, and a return to traditional underwriting standards."

Meanwhile, banks are facing what Douglas Berlon, Gallup's financial services global practice leader, calls "a perfect storm" of negative economic forces. "The credit downturn is unfamiliar territory for banks because the industry hasn't seen this convergence of factors since the late 1980s and early 1990s," he says. "Between the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the subprime loan and overall housing problems, possible recession, inflation and/or stagflation, and the weak dollar, some banks just aren't prepared for it."

No need for depositors to worry

The day Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae's stock tumbled, Secretary Paulson hastened to assure Congress that the companies are secure. The oversight provided by the Fed and the Treasury and the safety nets Congress has enacted since the Great Depression -- including federal deposit insurance -- make commercial banking a stable institution. "When you deposit your money in an FDIC-insured institution and an FDIC-insured account, your money is safe. That's not the case for a bank's stockholders," Jacobe says. "The stockholders pay a price when a bank fails, as its stock usually becomes worthless as the collapse takes place."

Moreover, banks are in much better shape now than they were when Gallup's measure of consumer confidence in banking hit its lowest point in 1991. "Before anyone jumps off the roof," Berlon says, "they should remember that banks and the economy recovered from previous downturns, including the savings and loan crisis, and there is no reason to think they won't recover this time."

So why are so many people worried?

According to Jacobe, "A strong banking system that has the trust of all Americans is essential to the nation's economic well-being. Every American must have confidence when they conduct a financial transaction that it will be completed in a routine manner without the risk of loss. Similarly, banking customers must be confident that when they put money in the bank in an FDIC-insured account, they will not lose money."

Ironically, the measures that banks must take to dig themselves out are the same measures that make them and their customers nervous. Though most banks have sufficient liquidity, a lot of them, like Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, have billions in bad debt on their books.

"As bad debt begins to pile up, banks react by saying, 'We're going to have to be a lot more conservative,' so they pull back and dramatically reduce lending money," Berlon says. "Then customers who may be a little bit behind on a loan get in trouble. And while they easily got loans every year for the past five years, they can't get them now. They get frustrated, angry, and worried, which results in a bad story to tell."

|

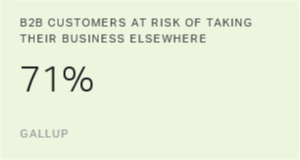

"The conversations that people are currently having with banks are not about expansion and new products. They are much more heated -- certainly for people who are feeling pressure about their day-to-day finances," Berlon says. "A negative cycle of spin happens, and people start hoarding, which is bad for revenue. If you don't trust banks, you don't trust banks' product lines, so banks are losing customers for their best profit producers, and customer engagement is declining."

What can bank management do?

The situation is precarious, but it does have some potential advantages. If banks handle conditions wisely now, they can regain short-term confidence, which can return long-term benefits. To do that, banks need to provide their customers with three things: transparency, reciprocal loyalty, and truly personal customer relationships.

Banks are already becoming more transparent. Public and congressional pressure in response to recent corporate scandals has forced a certain amount of financial openness. Banks that willingly drop the veil can gain a much-needed image of trustworthiness. "U.S. Bank is a great example. The president and chief executive, Richard Davis, basically opened up his financials to be more transparent," Berlon says. "If other banks do that, their consumers can regain trust that the bank isn't just trying to make a buck; they are legitimately charging a reasonable amount for a service."

As Berlon says, "Banks can be more transparent; they can go back to thoughtful, community-minded activity and dig deep to help local businesses grow. If banks do that and make sure they have products and services that meet the needs of those communities, they will absolutely win confidence back. But they must be transparent, honest, and thoughtful partners with all consumers of their business."

Loyalty exchange

One possible cause of low consumer confidence is the notion that banks got themselves into this mess and are making customers get them out -- that banks threw money around for years, and now that they're in trouble, they're putting the squeeze on reliable customers. So if banks treat their good, long-term customers as the valuable assets they are, it proves that banks aren't just "out to make a buck."

Reciprocal loyalty works much like transparency does to reassure consumers. "This is really a great opportunity for banks," Jacobe says. "Customers will stay with you forever if you're there when they need you." This is not as easy as it sounds. Banks are more conservative with loans, waivers, and interest rates these days. As banks shore themselves up, they risk treating customers like commodities. It's a natural reaction to corporate anxiety, but it will only make things worse.

"Every banking institution wants the customer to be loyal, but not every bank returns that loyalty," Jacobe says. "Banks could do a lot by being there for their good customers on both the savings and investment front and on the loan side. Of course, this means taking a longer term perspective toward their best customers. If banks are loyal to a good customer, they'll get loyalty back, and that's what banks need so badly right now. They'll need it even more in the future."

"What really worries me is that many banking executives will adopt an 'airline' approach to their customers," Jacobe says. "What I mean by that is the idea that 'We're incurring losses, so we need to minimize expenses, and customers will just have to live with it.' Instead, bank management needs to recognize that their customer base is their source of strength -- and now is the time to enhance, not reduce, their customer service quality and customer engagement."

True partnership

Another potential cause of consumer ire is the feeling that of all institutions, banks should have known better than to invest so much money in risky loans. The flip side of that, which is less discussed, is that banks understand economics well enough to know that shareholders expect returns, and subprime and riskier loans were extremely lucrative until the bottom fell out of the market.

Thus, a third way for the banking industry to regain consumer confidence is to put its specialized economic knowledge to work for customers, especially at the branch level. This method depends on the power of personal relationships -- the kind that people form with the folks at the bank. "Confidence is a measure of a relationship, and banking relationships form over time," Jacobe says. "It's more than confidence that the bank will be there; it's also confidence in the quality of service and the various ways the bank treats its customers."

|

Banks can help their customers by helping their employees understand the economic reality. This will allow bankers to promote a win-win situation for the customer and the bank. For example, bankers should be empowered to call their customers who live on investments -- many of them retired people -- when a better or safer option for investing comes up. They should tell small-business owners about government loans and alternative investment sources as necessary. They should go out of their way to share what they know with customers who can benefit from that knowledge.

That includes the customers they're just about to lose. "Banks can't turn away people at this time," Berlon says. "If you're telling people that you're foreclosing on their house, you can't make that conversation feel good. But you can help by getting them into credit counseling or connecting them with the right attorneys or the right CPA. You can get them to people who can help them out in a very meaningful way while they're mired in a really difficult situation."

Berlon doesn't think that the foreclosed upon will be so grateful for the financial advice that they'll stick with the banks that took their homes. Very few people are that magnanimous. But good advice can, at least, help people be less reluctant to trust their next banker, and it can help them get back on their feet.

That's the point. The consumers who are leery now will have money to invest next year or the year after. A bad banking experience now, whether personal or indirect, might drive that money away from banks and toward whatever seems more sound or customer friendly. And though someone who can't afford a loan shouldn't be given one, today's bankers should remember what banking veterans know -- that a negative situation is often temporary. A refusal phrased genuinely and honestly now can create goodwill that could be lucrative later.

So when the economy improves and consumers are more inclined to move money around, they might choose to punish their banks. "Once things settle down, and they will, people are going to say, 'I've had five thousand dollars in this bank, and the heck with them. I'm taking this money, and I'm going to put it in a mutual fund because my bank didn't do anything for me.' It's a very precarious spot for banks," Berlon says.

Is there anything the government can do?

Overall, Berlon and Jacobe give Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson high marks for the way they have handled the current financial crisis. "They did what they had to do and acted quickly," Jacobe says. "That is real leadership in the midst of a crisis situation."

On the other hand, Jacobe is highly critical of the way the IndyMac Bankcorp situation was resolved. "I don't think it was conducive to the nation's financial stability to force depositors having funds in the bank that exceeded the FDIC insurance limit of $100,000 to take a 'haircut' (a loss) on part of their deposits in the bank," Jacobe notes. "In my view, Congress and the FDIC need to find a way to avoid this problem. I think they should also consider increasing the federal deposit insurance limit to $250,000 as soon as possible so depositors -- particularly elderly Americans -- don't have to worry about spreading their money around to make sure it is federally insured. I hope that Congress will address this issue when they return from their August recess and before they leave to campaign for the November elections."