Story Highlights

- Indians' life ratings are especially low in the rural East

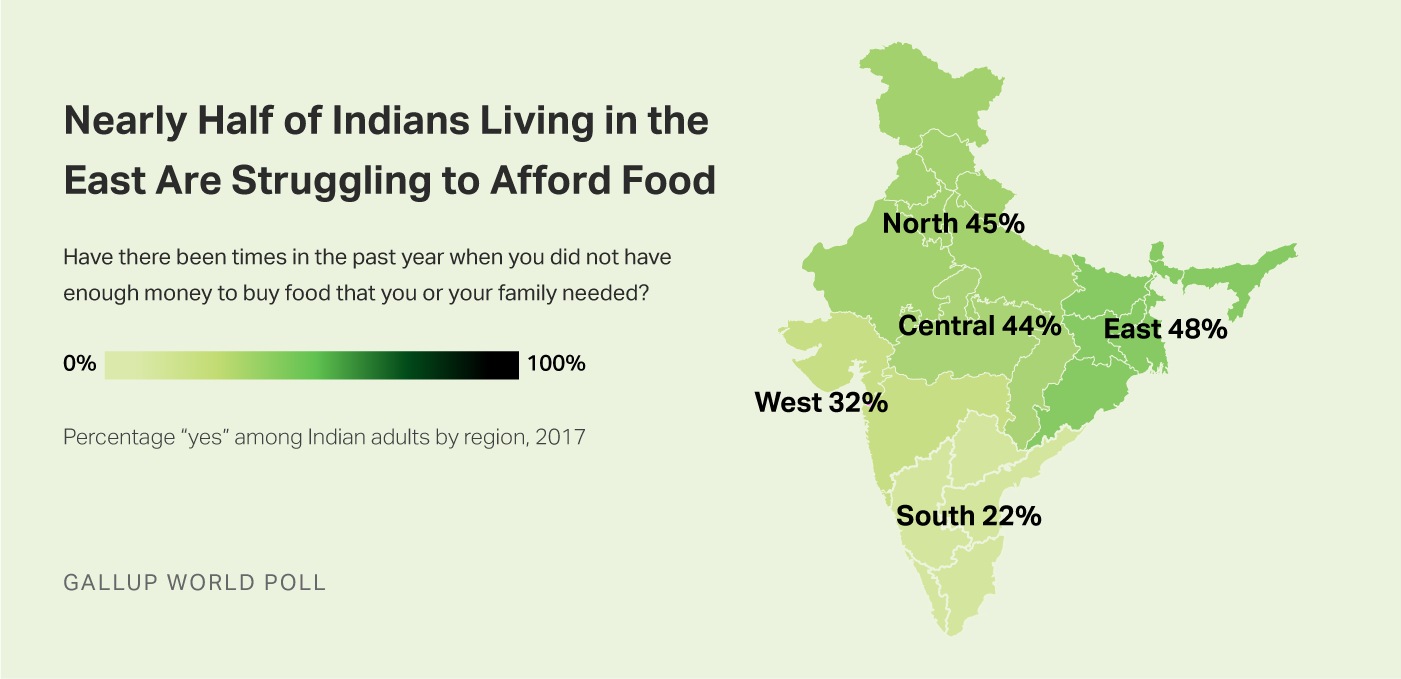

- Almost half of residents in the East struggle to afford food

- Regional disparities may affect 2019 parliamentary elections

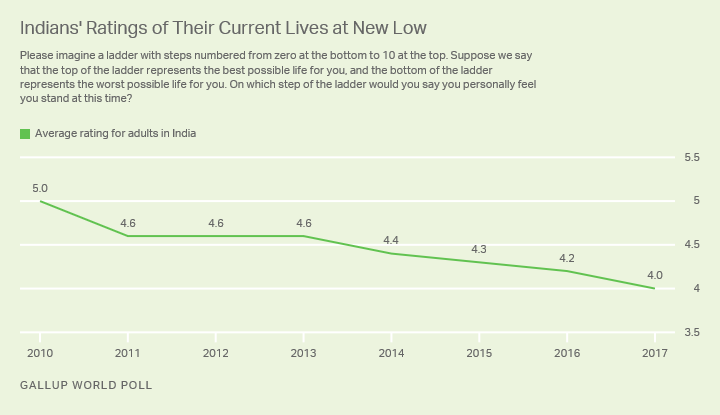

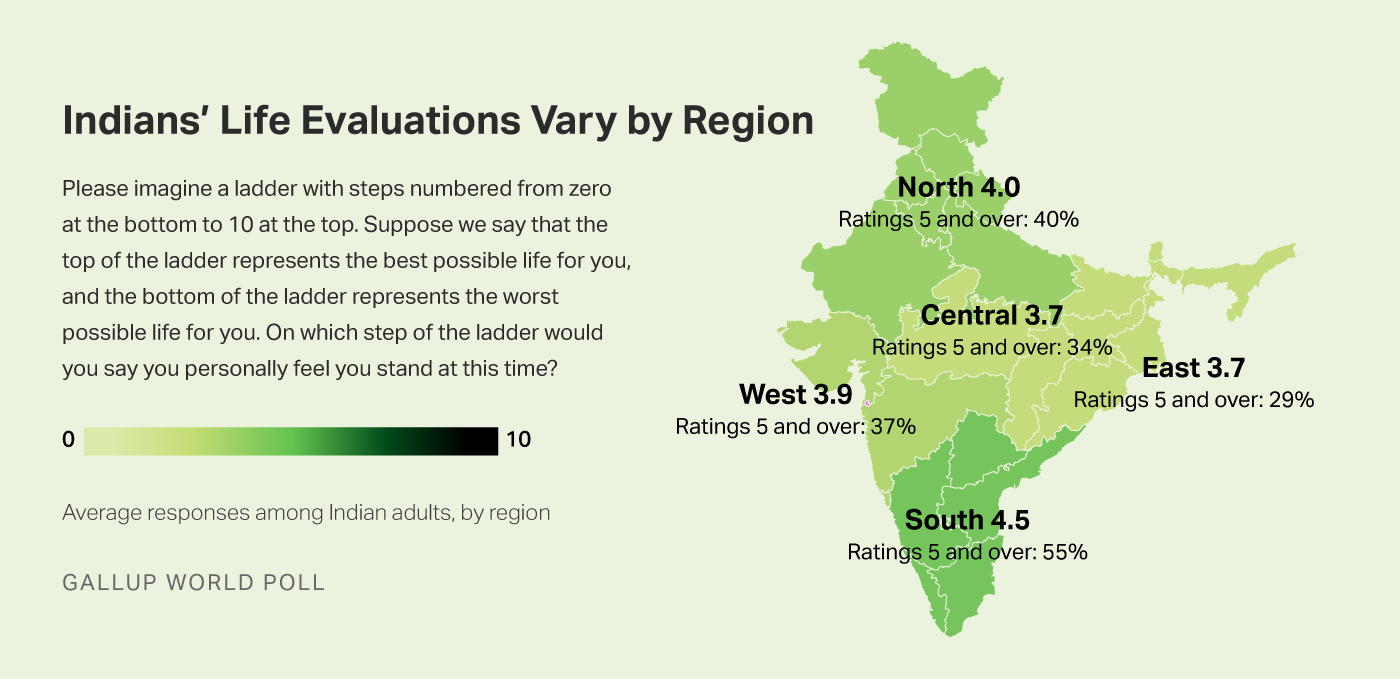

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Although Indians' ratings of their current lives nationwide are the worst in recent record -- averaging 4.0 on a 0-to-10 scale in 2017 -- their outlook depends a lot on where they live.

Highlighting significant regional disparities in one of the world's fastest-growing economies, residents in India's more urbanized South give their current lives an average rating of 4.5, versus 3.7 among those in the more rural Eastern and Central regions. While 55% of adults in the South rate their current lives a 5 or higher, about half as many in the East (29%) give ratings that high.

These low life ratings are particularly notable given India's economic momentum in recent years; the country's annual GDP growth topped 8% in 2015 before slowing somewhat to 7.1% in 2016 and 6.6% in 2017. Growth accelerated again over the course of 2017, and analysts expect it to be well over 7% again in 2018.

In many areas, however, most people aren't feeling the effects of that growth -- a finding that may have implications for the parliamentary elections to be held next spring. In 2017, the number of adults who said there were times in the past year when they did not have enough money to pay for food hit a high point of 37%, double the 18% who responded that way in 2012. Again, the results differ substantially by region; almost half of Indians in the East (48%) said in 2017 that they had had trouble paying for food in the past year, versus 22% in the South.

Regional differences in living standards and poverty rates have been stubbornly persistent as India's economy has grown. Economists have offered a number of possible explanations, including cultural and linguistic barriers that hinder internal migration, and poor governance in the country's less developed states, which makes it less attractive for businesses to take advantage of their cheap labor.

Not all of India's economic indicators have been trending more negatively in recent years. Indians were significantly more likely in 2017 than they were in 2013, before Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's election, to say it is a good time to find a job in their area (44% vs. 29%, respectively). And the proportion who feel their standard of living is improving edged up to 50% in 2017, from 44% in 2013. However, these indicators too are subject to large regional disparities -- for example, Indians in the South are twice as likely as those in the East to say it is a good time to find a job in their area (54% vs. 27%, respectively).

Implications

Modi recently predicted he would be re-elected with an even bigger parliamentary majority for his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in next year's general elections. As Indians' life ratings slipped, their support for Modi rose rather than fell: 79% of Indians said they approved of the job he's doing, the highest figure since he took office in 2014.

Modi's personal popularity may well insulate him from the mixed results regarding Indians' well-being and financial health. However, amid declining life evaluations and persistent hardship in much of the country, the same may not be true of local parliamentary candidates. The prime minister's party has already suffered regional losses in this year's by-elections, leading to speculation that it may be more vulnerable than many realize. If opposition parties successfully highlight the country's persistent disparities and mobilize poverty-stricken voters, the BJP may lose further ground next spring.

Survey Methods

Results are based on face-to-face interviews with at least 3,000 adults, aged 15 and older, conducted each year in India. For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is 卤2.2 percentage points. The margin of error reflects the influence of data weighting. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For complete methodology and specific survey dates, please review .

Learn more about how the works.