Unemployment and poverty alone did not lead to the overthrow of Egypt's government. It was the perceived difference between what should be and what was that created the driving force for the country's historic uprising.

Experience of hardship alone does not move people to resist. To shift from misery to a mass movement, people must first discover "moral anger and a sense of social injustice." This is according to Barrington Moore's seminal work Injustice: The Social Bases of Obedience and Revolt, a study of revolutions throughout history. In other words, he writes, the idea that the societal distribution of pain is unfair and the suffering is not inevitable as the prerequisite to action.

Many credit the successful ouster of Ben Ali in Tunisia for providing Egypt the necessary counter example to rid it of its culture of political fatalism. The citizens of Egypt harnessed their collective discontent and changed the social and political future of their country in the days spanning January 25 to February 11, 2011. Hundreds of thousands of citizens took to the streets in a peaceful stance of solidarity that resulted in one key outcome - an end to Hosni Mubarak's nearly 30-year rule.

If Tunisia's revolt provided the trigger for Egypt's uprising, the gap between what Egyptians expected and what they experienced provided the fuel.

Egypt's macroeconomic growth expanded the wealth of a small minority, but left many more with diminishing perceived access to this prosperity. Egyptians boasted the highest democratic aspirations of the region, but among the lowest in its actual practice. While many might have tolerated a paternal state-citizen social contract, where people accept less freedom in exchange for high-quality state-provided social services, Egyptians had neither. As Egyptian satisfaction with their personal freedom decreased, so did their contentment with state-provided necessities. This twin decline in attitudes suggests that in the eyes of many Egyptians the old regime had resembled more a prison warden than a generous if overprotective father.

This report describes underlying conditions that may have led to this popular revolt. The analysis is based on 优蜜传媒extensive surveys, including those conducted months before the uprising, through face-to-face interviews with citizens 15 years and older, male and female, educated and illiterate, from urban and rural areas across Egypt.

Economic Growth Without Prosperity

Egyptians' sense that they were not benefiting from the country's economic progress preceded the overthrow of Mubarak earlier this year.

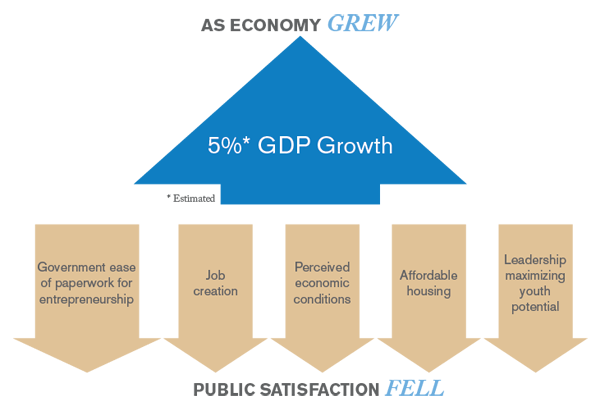

Although Egypt's GDP grew roughly 5% in 2010, one-fifth of Egyptians surveyed last year believed economic conditions were getting better. This compares to a median of 41% among their peers in regional middle-income countries. While a median of 31% of Egypt's economic peers said their economic conditions were "good" or "excellent," about half as many Egyptians (16%) said the same.

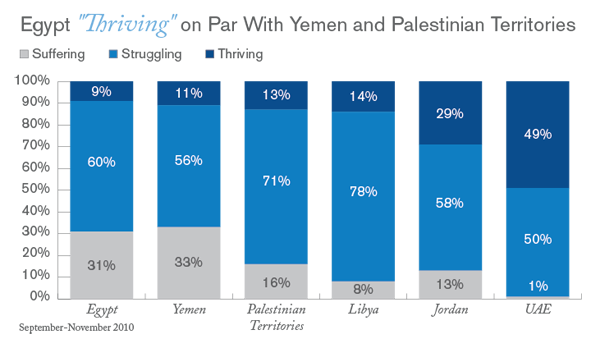

Additionally, in late 2010, roughly as many Egyptians (9 %) could be classified as "thriving" as residents of the Palestinian Territories (13%) or Yemen (11%) - two societies challenged by conflict and with a per-capita GDP less than one-half of Egypt's. 优蜜传媒categorizes individuals as "thriving," "struggling," or "suffering" based on how they rate their lives now and five years from now.[1]

This measure, referred to as "evaluative well-being," normally correlates positively with GDP growth, but did not in Egypt. Despite rising national wealth, the percentage of Egyptians classified as thriving declined since 2007. Only the richest Egyptians (the top 20% income level) rated their lives better in 2010 than in 2009.

Economic Growth Without Opportunity

Evaluative well-being and GDP correlate because citizens normally benefit directly from the economic growth of their country. For example, growing economies usually offer expanded entrepreneurship opportunities and accelerated job creation.

However, as Egypt's GNP per capita grew, its people's perceived access to this new wealth declined. The public expressed lower satisfaction along many dimensions, including the ease by which people could obtain the necessary permits to start a new business and thereby benefit from Egypt's economic development. Twenty percent of the public in 2010 said government made paperwork and permits easy enough for entrepreneurs, versus 26% who said the same in 2009.

The only entrepreneurship-related dimension that went up over the course of the year was new companies' ability to attract qualified employees - from 67% in 2009 to 74% in 2010. However, this might have had a negative economic explanation: the 25% youth unemployment rate that the IMF says exists in Egypt.

Egyptians also became less satisfied with many aspects of economic life that analysts expect to improve with macro financial success. For instance, about one in five said they were satisfied with Egypt's efforts to increase the number of quality jobs (down from one in four in 2009 and below a median of 31% among their economic peers).

In general, the survey revealed growing skepticism that Egyptian leaders care about young people. The percentage of respondents who said Egypt maximizes on the potential of youth declined to 29% in 2010 from 41% a year earlier.

The Shortcomings of the State

At the same time that many Egyptians were - from their own perspective - being left behind by the economy, they were also becoming much less satisfied with the social services their government provides.

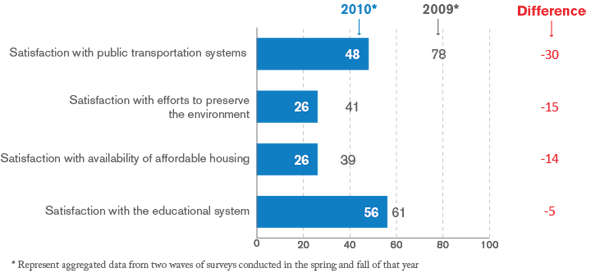

Forty-eight percent of Egyptians in 2010 said they were satisfied with public transportation systems. That was a dramatic fall off from 2009, when 78% expressed satisfaction with the public transit network of buses and trains in the nation.

Moreover, about one-quarter said there was enough good, affordable housing (down from 39% in 2009). Real estate price increases of more than 10% in 2010 may have contributed to the dissatisfaction in this area.

They were also less satisfied with efforts to preserve the environment, a question many Egyptians may have answered based on what was happening in their own neighborhoods with trash collection and sewage management. Twenty-six percent of Egyptians said they were satisfied with efforts to preserve the environment, versus 41% in 2009.

Another important social service that Egyptians perceived as in decline in 2010 was the educational system. The percentage of respondents saying they were satisfied with the primary, secondary, and tertiary school levels fell to 56% from 61% in 2009.

Unrealized Democratic Aspirations

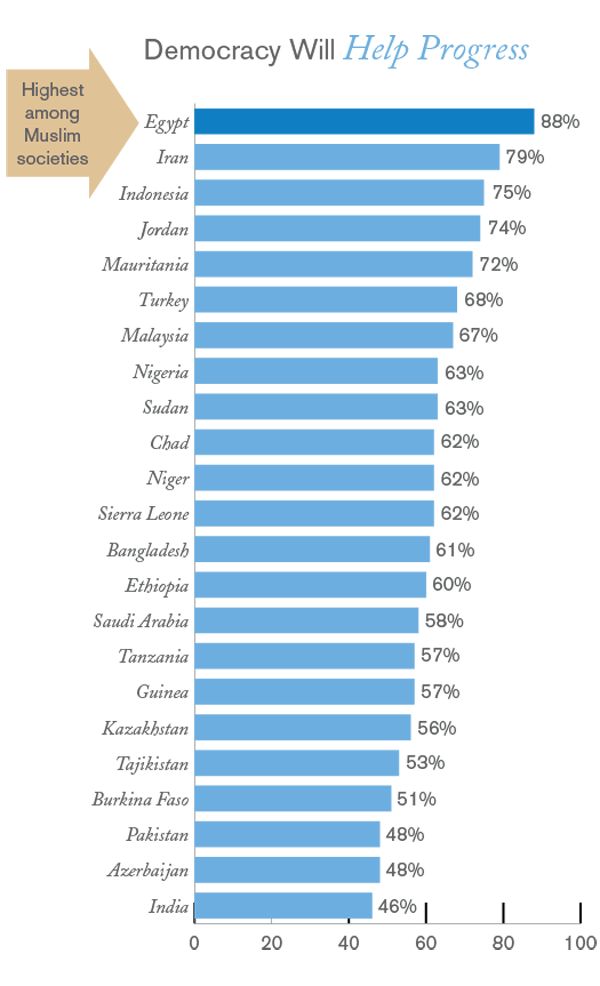

If growing discontent over the economy and social services played a role in the Egyptian revolution of 2011, so did the unmet political aspirations of the country's citizens. In the 2010 优蜜传媒survey, more than 80% of Egyptians said they agreed with the statement "Moving toward greater democracy will help Muslims progress." This was more than in any other Muslim majority society polled.

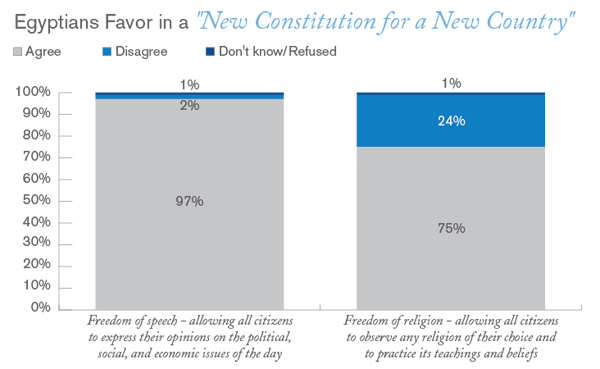

Egyptians also said one of the aspects they admired most about the West, besides its technology, was its democratic ideals. In 2009, 97% of Egyptians told 优蜜传媒they would guarantee free speech if they drafting a new constitution for a new country. Three-quarters said the same about freedom of religion.

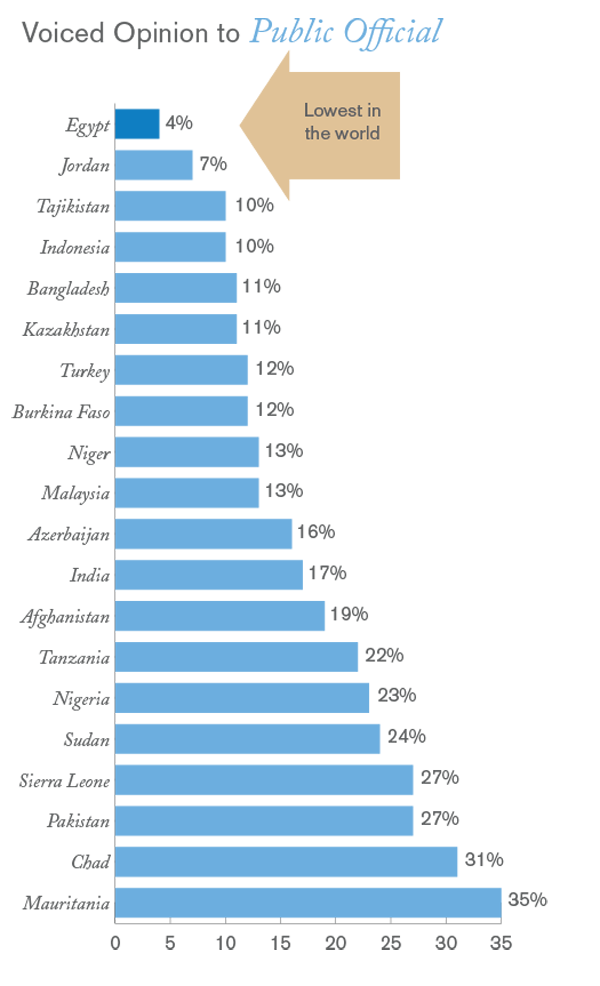

Pressed against this backdrop of democratic ideals was a very different reality. Whereas Egyptians were the most likely in the region to say democracy leads to progress, they were the least likely to practice it. Four percent of Egyptians said they had expressed their opinion to a public official, the lowest level in Gallup's 150-country database.

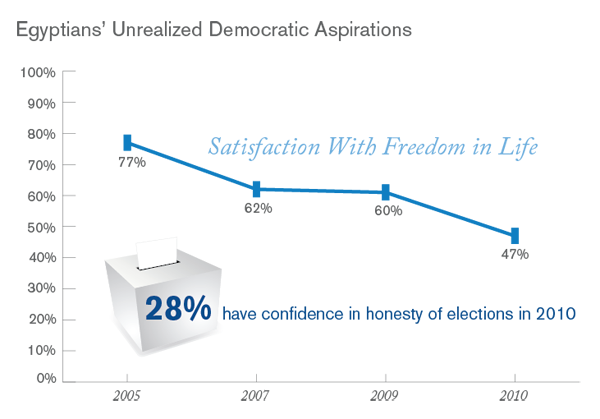

Egyptians had parliamentary elections in 2005 and in 2010, yet despite their growing discontent with state functions, very few sought out their parliamentary representatives to complain. This may be because a minority of Egyptians said they have confidence in the honesty of elections (28%). Perhaps because of these political frustrations, in the months before the uprising, levels of satisfaction with personal freedom in Egypt were also low, and they had been falling for years. Whereas 77% said they were satisfied with their personal freedom in 2005, in 2010 that number had fallen by 30 percentage points to 47%.

Moving Forward

Nathan Brown, a professor at George Washington University, wrote this shortly after Egypt's uprising succeeded in ending Mubarak's three decades in power: "For the first time in a generation, Arab societies look to Egypt for hope and inspiration."

Many observers agree. Egypt's size, strategic geographic position, cultural influence, and relative success in bringing about peaceful change make it an example for the region. If the most populous Arab nation builds a strong society based on the rule of law, it will influence the Middle East and North Africa region positively. If, on the other hand, Egypt's nascent revolution rolls back into an upgraded autocracy - or worse, the whole region will feel the negative impact.

As Egypt builds its future, its emerging leaders would do well to take stock of its past and the social and economic factors that propelled the revolution. The way Egypt goes, so goes the region, and for this reason the future of the oldest nation state matters to the whole world.

Survey Methods

Results are based on face-to-face interviews in Egypt with approximately 1,000 adults in each country per survey administration, aged 15 and older, in 2009 and 2010. Surveys in Egypt in 2009 took place March 7-22 and Aug. 11-19; in 2010, they were conducted March 13-23 and Sept. 25 to Oct. 26. For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is 卤2.5 percentage points.

All other results for countries mentioned in this article are based on face-to-face interviews in 2010 with approximately 1,000 adults in each country per survey administration. For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is 卤2.6 percentage points. Surveys in Arab Gulf countries were conducted with nationals and Arab expatriates. The margin of error reflects the influence of data weighting. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

[1] The Life Evaluation Index measures respondents' perceptions of where they stand now and in the future. Building on the earlier work by Hadley Cantril and The Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale, 优蜜传媒measures life satisfaction by asking respondents to place the status of their lives on a "ladder" scale with steps numbered from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates the worst possible life and 10 the best possible life. Individuals who rate their current lives a "7" or higher AND their future an "8" or higher are "thriving." Individuals are "suffering" if they report their current AND future lives as a "4" and lower. All other individuals are "struggling."