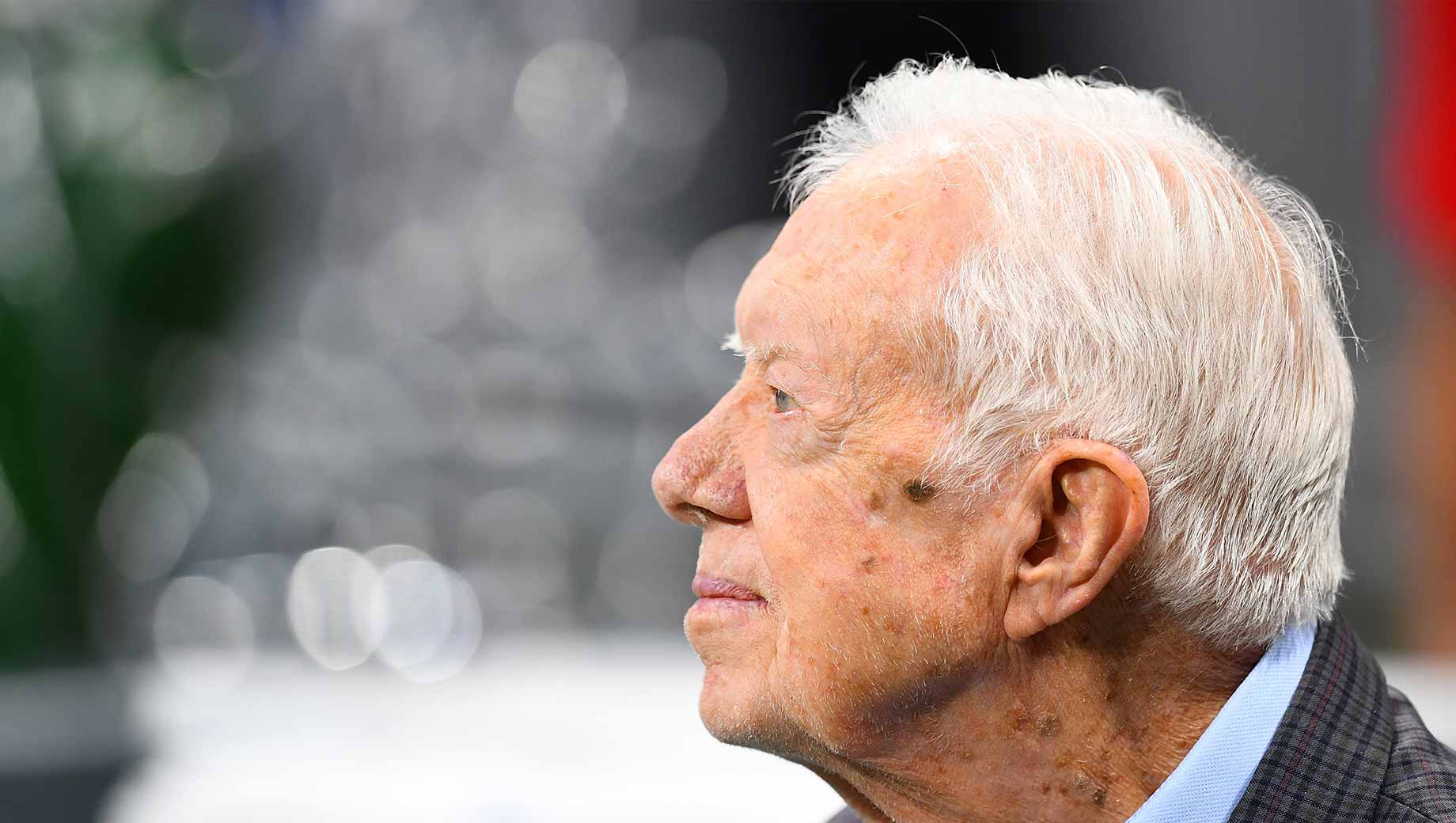

The recent announcement that former U.S. President Jimmy Carter entered hospice care has focused renewed attention on the 98-year-old Carter’s life, career and character. Part of that attention centers on his religion, a key element in his public persona since he first became nationally prominent. As a New York Times article noted in 1976, “Carter's Evangelism Putting Religion Into 优蜜传媒 for First Time Since '60,” calling Carter “a deeply committed evangelical Christian.”

That legacy has endured. As Foreign Policy magazine headlined in a recent retrospective, “Jimmy Carter Was America’s Evangelical-in-Chief,” going on to say that “Carter’s declaration that he was a born-again Christian had provoked incredulity from the national press corps, but the statement resonated with many Americans, including evangelicals themselves.”

Carter, in short, is a Protestant for whom religion is very important and one who at various times has been referred to as a Southern Baptist, an evangelical and as born again. Yet much has changed since Carter was elected president. He is no longer a Southern Baptist; it’s not clear that he would claim the evangelical label if interviewed today in a typical survey, and he certainly does not hold a number of the beliefs usually associated with evangelicals.

Carter’s religious pilgrimage highlights the challenges researchers face in attempting to segment the elusive group of Protestants and other non-Catholic Christians who are loosely referred to as evangelicals. As I discussed in a 2018 analysis, and as has been the topic of much scholarly debate, there is no single agreed-upon way to define who is and is not an evangelical. Baylor University historian Thomas Kidd, for example, noted in his book Who Is an Evangelical?, “The word evangelical itself is a source of confusion: scholars, journalists, and the public can’t seem to decide what it means,” adding, “Trying to pin down evangelicals can be maddening.”

Maddening or not, researchers have typically tried to identify evangelicals using one of three methods. As will become clear, it’s uncertain how Carter fits into each of these categorizations today.

Defining Evangelicals Using Self-Identification

The most commonly used method for putting people into an evangelical bucket is the simplest: asking respondents if they would describe themselves as evangelical. This certainly has research value. But as an effort to segment a group that shares common religious beliefs and practices, it falls short for several reasons.

First, studies reinforce the general conclusion that those who self-identify as evangelical in surveys do not necessarily share evangelical beliefs and practices that experts associate with the term. As researchers Leith Anderson and Ed Stetzer pointed out a few years ago, “Many Christians hold evangelical beliefs but don’t call themselves evangelical; many Christians call themselves evangelical yet don’t hold evangelical beliefs.”

If the research objective is to isolate a group of non-Catholic Christians who share specific beliefs and practices, then the use of self-identification as an evangelical faces significant challenges. The researcher does not know and can’t determine without further questioning who self-identified evangelicals are, in terms of what they believe or how they practice their religion.

There are other problems. The term evangelical is widely used in current culture and discourse as a synonym for religious Christians who are conservative Republicans. Thus, respondents, asked if they identify as an evangelical, may answer the question not in terms of their religious beliefs and practices, but in terms of their politics. Respondents who are conservative Republicans may be at ease with identifying with the term evangelical because their personal identity corresponds to the term’s associations in the political arena. But those who are not politically conservative may abjure the term for the same reason. Then, when researchers find that respondents who say “Yes” to the evangelical self-label are disproportionately likely to be conservative Republicans, we have a textbook example of circular analysis.

An added wrinkle comes with the fact that many researchers, including 优蜜传媒and Pew Research, have historically asked respondents if they would describe themselves as “evangelical or born again,” thus conflating two different concepts (a double-barreled question). 优蜜传媒research and a recent study by University of Pennsylvania political scientist Michele Margolis show that these two terms are by no means synonymous, with significantly different percentages of the population agreeing that each term describes them when asked about separately. Self-description as born again is clearly a belief question, while self-description as evangelical is a question with many external overtones and connotations. This means a staple trend question used by prominent researchers has a layer of complexity that complicates its interpretation.

Of course, at some level, self-identification into a labeled category, no matter the ambiguity that surrounds that category, has research value. For example, there is no agreed-upon precise definition of what it means to be a liberal or a conservative, but knowing how a person describes themselves tells us how they see themselves fitting into the contemporary political landscape.

So, self-identification as an evangelical provides useful information. But its use as a way of describing a group based purely on that group’s religious beliefs and practices has less value.

I’m not aware of any recent situations in which Carter was asked directly if he would describe himself as an evangelical. But I don’t think it is certain that Carter would answer “Yes” in a survey today (or at least, he would attempt to dissect the term and explain what he understands about how the term is used).

Defining Evangelicals by Beliefs and Practices

Another method used to define evangelicals in survey research is to ask about Protestant respondents’ beliefs and religious practices, and then to segment, based on whether those beliefs do or do not meet various predetermined criteria of what constitutes an evangelical.

This makes sense at a general level. But there is, unfortunately, no agreement on exactly which beliefs and practices form the necessary criteria for being an evangelical. Scholars and researchers create particular lists (including, for example, such things as belief in the necessity to have a born-again experience, belief in the authority of the Bible, belief that Christ died on the cross to atone for sins, and so on), but each researcher or group ends up with differing criteria.

Plus, even if there is agreement on theological criteria for classifying someone as evangelical, there is the challenge of attempting to operationalize those criteria into question wording that accurately reflects the underlying concept in a way respondents will understand.

Where does Carter fit in? He might qualify as an evangelical, based on some of the beliefs and practices religious scholars use to define an evangelical, but certainly not all. In a remarkable 2012 interview with Southern Baptist Seminary President R. Albert Mohler Jr., Carter indicated that he does not believe the Bible should be interpreted literally, word for word; that homosexuality is not a sin, and that he would welcome gay people into his church; and that women should be equal with men when it comes to ordination as ministers. All of these would disqualify him from being considered an evangelical, according to at least some religious authorities.

Defining Evangelicals Using Denominational Affiliation

A third method of identifying evangelicals is to probe American Protestants for their exact denominational affiliation and then, using predetermined criteria, assigning those individuals to an “evangelical” category based on assumptions about their denomination.

This method has a number of problems. For one, given the hundreds of U.S. Protestant denominations, it is extremely complicated and time and work intensive to attempt to drill down in a survey and isolate Protestant respondents’ denominational affiliation. Pew Research last attempted this procedure in its 2014 Religious Landscape Study. Pew’s denominational questions for that study take up eight printed pages, with complex probes and follow-up questions -- hardly the recipe for a survey item that can be routinely inserted into ongoing survey research (and probably part of the reason Pew hasn’t attempted it since).

Plus, decisions on which denominational identity is or is not evangelical are to some degree arbitrary, particularly when it comes to subdivisions within broader categories (e.g., deciding which of the many Methodist branches should be considered evangelical). And, even within a denomination usually classified as evangelical, such as the Southern Baptists, there are individual churches that don’t fit an evangelical mold.

There is also group attribution error, which arises when one assumes that every person who identifies with a particular denomination personally adopts the belief structure of that group. This may be a reasonable assumption on average, but certainly not in all cases. An individual who identifies with a denomination classified as evangelical is not always personally evangelical. And individuals who identify with a nonevangelical denomination may themselves be very evangelical at a personal level.

In addition, the increase in nondenominational churches in American Protestantism today leaves a significant group that can’t be directly or easily classified into an evangelical category based on history or tradition (unless one makes the tenuous assumption that, for example, any and all nondenominational Protestant churches are evangelical).

As noted above, Carter famously announced in 2000 that “After 65 years, I can no longer be associated with the Southern Baptist Convention.” He now worships at the small Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains. Maranatha may retain some ties to the Southern Baptist Convention, but it would be a mistake if pollsters linked Carter’s membership in that church to an assumption that, as a result, he is an evangelical.

Bottom Line

Inevitably, Carter will be identified as an evangelical in the obituaries that will flow forth after his passing. In so doing, commentators, journalists and eulogists will gloss over the uncertainties and confusions about the use of that term. It is fair to say that Carter grew up and remains very religious, that he is a Southern Protestant, and that his Baptist faith, particularly in his early years, shared a tradition of what historians have labeled as evangelical. But the claim that Carter at the end of his life remained an evangelical at least needs further explanation and discussion, given the challenges in defining exactly who is and is not a member of that complex category.

In the face of this ambiguity, one suggestion is to move away from the use of the term evangelical in routine survey research and routine discourse. Instead, a useful and straightforward procedure could be to segment American Protestants on the basis of their religious activation, creating groups for whom religion is important in their daily lives and thus likely to affect other aspects of their lives (including politics and positions on policy issues) and groups for whom religion is more incidental in their daily lives. Thus, instead of talking about evangelical support for this or that political candidate or policy, the talk could center on religiously activated Protestants for whom religion is very important in their daily lives. If the objective is to segment the Protestant population into meaningful groups that, in turn, help explain other variables of interest, religious activation -- the actual impact of religion in one’s daily life -- deserves consideration.

To stay up to date with the latest 优蜜传媒News insights and updates, .