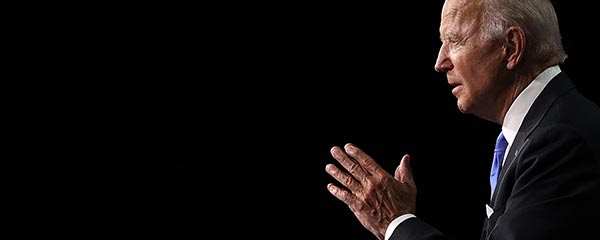

Two recent surveys have updated the voting intentions of White Protestant evangelicals. that President Donald Trump's margin over Joe Biden among registered voters within this group is a substantial 78% to 17%. A a similar margin, with Trump ahead of Biden among White Protestant evangelicals, 79% to 20%. Both of these levels of Trump support are similar to what he received in the 2016 election according to . But, as I have reviewed previously, any time we talk about evangelicals in America today, questions arise, making this a good time to update some key points in reference to this important but often misunderstood group.

Who exactly are evangelicals? Baylor University historian Thomas Kidd, an authority on the history of evangelicalism, notes that the term evangelical has been in use in the United States at least since the early 1800s, although with widely different connotations and without a consensus as to who or what evangelicals are. As Dr. Kidd says in his book , "The word evangelical itself is a source of confusion: Scholars, journalists and the public can't seem to decide what it means," noting that "trying to pin down evangelicals can be maddening."

Dr. Kidd goes on to point out that "some Christians who seem to be evangelicals do not describe themselves as such. Others (especially Whites) who don't necessarily hold evangelical beliefs or regularly attend church nonetheless tell pollsters that they are evangelicals."

Survey Researchers' Approach

Survey researchers have tackled this challenge of reducing the confusion and identifying evangelicals in three basic ways over the years. The first uses individuals' specific beliefs, experiences and intimate religious connections as the criteria for inclusion as an evangelical. For example, Dr. Kidd defines evangelicals as those who self-identify as born again and Protestant, and who "cherish the Bible as the Word of God and who emphasize a personal relationship with Jesus Christ through the Holy Spirit." Barna Group, a well-known religious research organization, adds considerably more complexity, arguing that to be an evangelical, an individual needs to respond affirmatively to .

The second approach is to use an individual's denominational identity as a surrogate measure of being an evangelical. This is a challenging procedure given the huge number of Protestant denominations in the U.S. today. It requires probing Protestants to obtain their specific denominational identity, plus a post-survey process of classifying denominations into categories based on decisions about which denominations are, and are not, evangelical. Additionally, not all members of any one denomination are the same. The Southern Baptist denomination, for example, certainly has an overall evangelical thrust, but individual Southern Baptists can still range widely in their underlying beliefs and practices. The same goes for Presbyterians and other mainline denominations that tend to be theologically moderate but include those who are quite evangelical.

Both of these research methods are cumbersome and difficult to use on an ongoing survey basis where space and time are at a premium. Pew Research, for example, uses the denominational approach in its huge (last conducted in 2014) but not as part of its ongoing research.

Most pollsters who actively want to include a measure of evangelicals in their research today thus opt for a third method -- approaching the question of "Who is an evangelical?" by asking people if that label does or does not fit their view of themselves. The most common such self-report question asks survey respondents if they identify as "born again, or evangelical." This is the question used most frequently by Gallup, and by both the Pew Research and Washington Post/ABC News surveys whose recent results I discussed above.

This approach has the great advantage of being simple and to the point but still involves some ambiguity. We don't have in-depth knowledge of exactly why some people identify with the term "born again, or evangelical" and others do not, and it's possible that answers to the question today reflect cultural stereotypes along with self-assessments of personal religion.

The Limits of Self-Reporting

Responses to the binary question asking people if they identify as evangelical are clearly reflective of underlying religiosity. Some 61% of White Protestants in 优蜜传媒data from 2017 to 2019 who said yes to the "born again, or evangelical" question reported attending religious services every week or almost every week, compared with 25% of those who said they were not "born again, or evangelical." And 78% of White Protestants who identified as evangelical said religion was very important in their lives, compared with 33% of White Protestants who did not identify as evangelical.

In other words, whatever else White Protestants' affirmative response to the evangelical question may reflect, it is strongly related to frequent church attendance and the personal importance of religion in one's daily life. Thus, I think it is fair to say that when we use the term evangelical in a political context today, we are basically talking about White Protestants who are very religious.

The frequent use of the term evangelical in our cultural discourse could also be a factor in how people respond when asked if it applies to them. If we assume that the American population at large is aware of the common connection between evangelicals and conservative, Republican support for Trump, we can assume that this association could affect a respondent's willingness to self-label as evangelical.

It may be that some Americans interpret a question asking if they identify as evangelical as one asking if they identify as belonging to a group of individuals who are conservative, Republican supporters of Trump. Those who see themselves fitting into the latter would say yes; those who don't would say no. Thus, the high correlation between White Protestant evangelical identity and support for Trump could reflect in part the assumption that those who accept the label evangelical are accepting a label connoting conservative political leanings.

Why Do Evangelicals Support Trump?

Then there is the ongoing question of why White Protestant evangelicals support Trump at the level they do (this is one of the most common questions I get). Of course, as I have shared, this is really a question focused on three groups: Why do Whites support Trump at a level significantly above that of non-Whites? Why do Whites who identify as Protestant support Trump at a level significantly above the level of non-Protestant Whites? And then, finally, why do those who are White and Protestant and who self-identify as evangelical support Trump at an even higher level?

The answers to those questions are complicated and arise from the complex historical structure of the American political system across racial and religious groups. (For example, why do Black Americans overwhelmingly support the Democratic presidential candidate in election after election? Why do Jewish Americans strongly support Democratic presidential candidates? Why do a majority of Mormons support the Republican presidential candidate? And so on.) There are a number of important reasons as to why highly religious White Protestants who define themselves as evangelical have come to the point where they tilt strongly Republican in their political behavior. Many of these have been examined in research and books focused on matters ranging from to in America.

The main point I would make here is that these structural patterns of association between evangelicalism and conservative politics were well in place before Trump came onto the presidential scene. Whites who identify as Protestant and as evangelical have long supported Republican candidates. Trump is simply the latest in this line.

In short, the expected direction of the presidential vote of White Protestant evangelicals is Republican. The question of interest is what it would take to change this baked-in pattern. Most particularly, I am often asked about the possible defection of evangelicals from supporting Trump in this election due to the fact that his religious history and personal behavior is far from the typical candidate who appeals to religious voters.

As we have seen, there has certainly been no such defection to date. Trump has helped shore up his evangelical support with special efforts to push policies and executive orders that resonate with rank-and-file evangelicals and their leaders -- policies related to abortion (including Trump's recent nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court), religious freedom, school choice and Israel.

Trump also directly addresses evangelicals -- and in particular, evangelical leaders -- and asks for their vote, and a number of well-known evangelical leaders have responded by expressing public support for his presidency and his reelection bid. Trump has also and as a potential foe of religious Americans should he be elected.

Bottom Line

Trump continues to have a lock on the vote of the substantial majority of White Protestant evangelicals in this presidential election. At the same time, unlike previous Democratic candidates, Biden is attempting to alter the Republican hegemony over the evangelical vote. Biden appointed evangelical Josh Dickson as his , and Dickson is in turn promoting "Believers for Biden." Biden has emphasized his personal (Catholic) faith in many venues and speeches. Some 1,600 religious leaders, including many evangelicals, . But the data show that while Biden's efforts may have some impact on the Catholic vote, and perhaps may depress the turnout of evangelicals, structural factors and Trump's blandishments to White Protestant evangelicals apparently are holding the voting preferences of this group firmly in place.