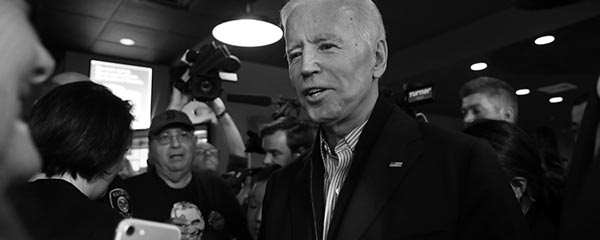

The most significant storyline coming out of the June 27/28 Democratic primary debates was Sen. Kamala Harris' attack on front-runner Joe Biden's opposition to school busing in the 1970s, while he was serving as U.S. senator from Delaware. Harris referred to her own positive experience as a young black girl being bused in California in 1969 and asked Biden: "Do you agree today that you were wrong to oppose busing in America?"

Biden equivocated in his response, attempting to thread the needle between his opposition to federal court-ordered busing and local busing. Most observers scored this exchange as a victory for Harris, and some horse-race polling (but not all) conducted after the debate showed Biden losing ground and Harris gaining as the preferred Democratic presidential nominee.

Of course, as I have discussed in some detail, Biden's extraordinary longevity as an elected official at the federal level (stretching from 1973 to 2017) means that he was taking positions on issues in contexts that are ancient history to many voters today. His busing position in the 1970s is one of these.

The environment of the 1970s pertaining to race relations, busing and Biden . My focus here, however, is the public opinion context in which Biden was operating in that decade.

While we don't hear so much about busing these days (the last time ���۴�ýasked about busing in a national survey was in 1999), it was a more prevalent polling topic in the 1970s. I find at least nine different times during the 1970s when ���۴�ýasked about busing, using a variety of question formats and contexts. The key finding: A significant majority of Americans disapproved of the concept of busing in every poll ���۴�ýconducted during the '70s, with most polls showing 70% or more who registered a negative opinion.

Biden's opposition to busing in the 1970s, in short, was consistent with majority national public opinion. (���۴�ýdidn't conduct polls in Delaware in the 1970s on the topic of busing, but apparently as nationally.)

Some, presumably including Harris, would assert that public opinion should not have mattered; that Biden should have courageously supported busing even in the face of majority public disapproval. This position assumes that Americans' opinions on the matter should have been ignored. This is what I call the "Profiles in Courage" position, after John F. Kennedy's in which he (and his coauthor Theodore Sorensen) extolled the courage of U.S. senators who took positions against prevailing public opinion and partisan pressure.

The conclusion that Biden was in the wrong on busing in the 1970s is built on the assumption that he was serving not so much as a delegate of the people but as a trustee, sent to make his own decisions on policy matters, regardless of the public's views. But is complex, and one that doesn't necessarily yield easy answers.

Additionally, opposition to busing as a mechanism to achieve higher levels of racial equality in education doesn't necessarily imply opposition to the concept of integration.

One example comes from the 1999 ���۴�ýpoll on the topic. In that survey, a large majority of Americans opposed "… transferring students to other schools to create more integration, even if it means that some students would have to travel out of their communities to go to school." But in the same survey, by a proportion of 59% to 28%, respondents said that more, rather than less, should be done "to integrate schools throughout the nation." In other words, Americans supported the concept of integration, while disapproving of busing as the means to carry it out. This is essentially the position Biden has taken. Other research also shows that , even while equivocating on specific policies used to implement that goal. A majority of Americans supported the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision from the start.

So should Biden be taken to task for going against public opinion on the issue of busing in the 1970s? Sen. Harris certainly would say "Yes," and that his failure to support busing in the tumultuous years of the 1970s was an indication of his weak historical support for civil rights and efforts to reduce race-related inequality. Others, however, may say that Biden was doing his job as a representative of the people while in office.

Biden's Cooperation With Eastland and Talmadge

Harris and others have also attacked Biden's references to his historical cooperation with two Southern Democratic senators, James O. Eastland and Herman Talmadge, both ardent segregationists. Biden made this point to showcase his skills at working with those of differing political views, under the assumption that these skills are needed in today's time of extraordinary political partisanship. Critics say Biden's proud claims of working with segregationists underscored his insensitivity to race relations and lack of commitment on matters of civil rights.

Biden's underlying point about the need for political compromise, however, is one with which Americans tend to agree -- and based on her post-debate comment, one that Harris agrees with in principle as well. Only a relatively small minority of Americans favor elected representatives who stick to their principles rather than compromise.

Of course, compromise by nature involves dealing with those who have principles that differ from one's own, some of which are presumably abhorrent to the individual doing the compromising. The current lack of across-the-aisle cooperation is to some degree responsible for the position Congress is in today, with political stalemate; a federal government shutdown in late 2018 and early 2019; the of government this fall; a 19% congressional approval rating; and a situation in which only a third of Americans say that the American political system makes them proud.

Critics may be correct that Biden erred in referring to his cooperation with segregationist senators because it showed insensitivity to racial matters and the negative impact of Southern segregationists, who slowed down civil rights legislation for many decades. Biden presumably could have referred to his cooperation over the years with other senators of different political persuasions. Still, it's important to recognize that Americans believe that dealing with one's ideological opponents in an elected body is necessary, even if their views are starkly different from one's own. Americans want more cooperation in Washington, not less.