It's a truism in politics that labels matter. When President Barack Obama and his Democratic allies in the Senate and House passed healthcare reform legislation in 2010, they developed an official name for the law that they thought would convey the positive benefits of the bill: "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act." That name has often been shortened to "Affordable Care Act" in the years since its passage, but the bill has also come to be known as "Obamacare," a name frequently used by Obama himself. Others simply call it the healthcare law.

The political news site Politico called our attention to the importance of these labels in a story on Tuesday reporting that the Obama administration has shifted to a sole focus on the label "Affordable Care Act." Politico that, "The president didn't say 'Obamacare' once during his nearly hour-long news conference last week, while he referred to the 'Affordable Care Act' a dozen times."

It is likely that White House strategists developed the new approach -- perhaps based on internal polling -- under the assumption that the more formal name "Affordable Care Act" would help in the current toxic environment of the negative publicity associated with the troubled rollout of the healthcare exchanges. Additionally, The White House may think that, at this juncture, it is best not to directly reinforce Obama's association with the law.

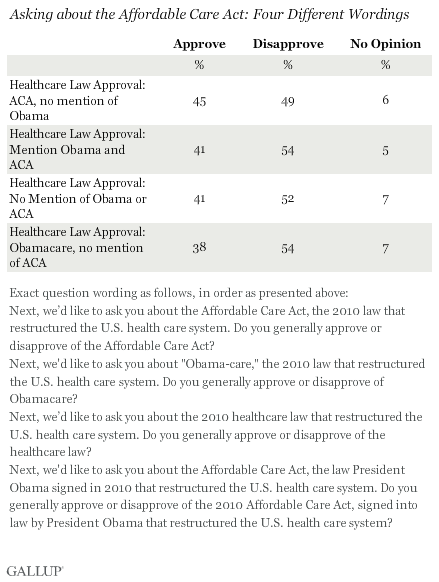

New 优蜜传媒research helps shed light on this issue. We have just completed an experimental test of four different ways to label the healthcare law. The results show that labels do make at least a marginal difference in the degree to which respondents approve or disapprove of the law.

优蜜传媒read the same basic question to four randomly selected groups of the 优蜜传媒Daily tracking sample each night between Nov. 4-17 -- but with four different descriptions of the law. A total of 1,725 to 1,885 respondents received each version of the question.

Here are the four variations in the wording:

The results of this experimental test show that the healthcare law descriptions can make a difference in the responses. Only mentioning the Affordable Care Act yields the highest support (45%), while only mentioning Obamacare yields the lowest support (38%). Support for the law when using the other labels falls in between, at 41%.

These results suggest that the Obama administration's decision to shift to Affordable Care Act as their label of choice and to avoid using Obamacare would appear to be a branding strategy that works in the administration's interest. Clearly, all else being equal, the words "Affordable Care Act" engender a modestly more positive reaction than the term Obamacare.

Approval of the healthcare law using the wording that mentions both Affordable Care Act and Obama, and the wording that mentions only the healthcare law -- which can be thought of as balanced approaches -- comes in between the first two reviewed above.

Overall, the outlier among these four labels is the use of "Affordable Care Act" without any other identifiers, in particular without mentioning Obama. Although Americans still end up more likely to disapprove than approve of the law using this wording, the margin is smaller than it is when asking about it any of the other three ways.

Gallup's trend uses the version which includes both Affordable Care Act and Obama -- which seems to us to be the most balanced approach. Of course, regardless of wording, the key to measuring changes in attitudes is holding that wording constant with each measurement over time. This approach rules out differences in question wording as a cause for changes. Still, the current research indicates that the absolute value of approval or disapproval measures of the healthcare law could be at least slightly different depending on the wording used.