Proposals to increase the federal minimum wage continue to come before Congress, and continue to generate intense controversy. Two years ago, when the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2004 was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives, Randel K. Johnson of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said of the bill, "It is [small] businesses, the backbone of our economy, which will be hurt the most by this proposal." And during a push for an increase in the minimum wage in 2002, the National Federation of Independent Business stated: "Given the precarious state of the economy, a minimum wage hike would be the worst thing that could happen for small-business owners." Both times, the efforts to increase the federal minimum wage went up in flames, and a similar bill was rejected by Congress this year.

|

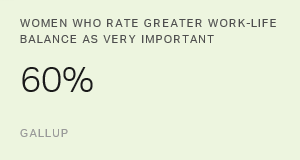

In light of this strong opposition, one would think that $2.10 -- the amount that this year's bill would have hiked the federal minimum wage -- would horrify small-business owners. As it turns out, they really don't seem to care that much. In March, the Wells Fargo/优蜜传媒Small Business Index survey asked small-business owners about the minimum wage. A significant percentage, 86%, said the minimum wage has no effect on their businesses. Few of them (14%) would be more likely to hire a new employee for $5.15 an hour, which is what the minimum wage has been since 1997, than to hire that person at a higher wage (80%). Forty-six percent even said the minimum wage should be increased. (See "Minimum Wage Has No Impact on Small Business" in the "See Also" area on this page.)

The vehement opponents of the minimum wage, such as those quoted above, usually say the first victims of a minimum wage hike are small-business owners. Small-business owners, Gallup's research shows, might well disagree. A wage hike would nevertheless have some effect on the economy. The question is, how much?

Meanwhile, millions of Americans are struggling to get by on less than $10,000 a year before taxes. What would an extra $2.10 an hour mean to them?

These are likely to remain hotly debated questions, particularly as Democrats seek to gain control of the House or Senate this fall -- and Dennis Jacobe, Ph.D., Gallup's chief economist, has given them a lot of thought. In this Q&A, he assesses the potential impact of a minimum wage hike on the economy and explores other pressing political issues, such as illegal immigration and job offshoring, whether there really is such a thing as a "living wage," and a little-exploited advantage small-business owners have over the big guys.

GMJ: The government has increased the minimum wage several times since its inception. What has been the impact on the economy?

Dennis Jacobe, Ph.D.: In the past, there have been examples when minimum wage increases could clearly be felt throughout the economy. There were two effects: One was "wage-push inflation," and the other was that some low-skilled people who were not worth the new minimum wage found it harder to get a job. Companies couldn't afford to pay very low-skilled workers and get the job done. And finding enough skilled workers is still a problem for small businesses.

GMJ: Why have states established their own state minimum wages that are higher than the federal minimum wage?

Jacobe: Each state can set its own minimum wage, and generally it's not an issue because the federal minimum wage has often been higher than most states'. But it's been almost a decade since the national minimum wage has been raised. So there's a lot of pressure to boost the minimum wage based on the philosophy that it should be at a wage level that provides at least a minimum living standard for the person who's working a minimum wage job.

|

GMJ: And that brings up the question of a "living wage," a notion that has taken hold around the country.

Jacobe: Economists talk about the living wage, but it's an amorphous kind of concept, because what's necessary is in the eye of the beholder, to some degree. A living wage depends on who's making it, where they live, and their family situation. What about two-worker households? You combine two incomes, and that's a different situation. Some minimum-wage workers are young and still living with their families.

So the question becomes, how many families of what size are really trying to live on a minimum-wage income, and where are they living? It's been a long, arduous debate.

GMJ: But 40 hours a week at $5.15 an hour is still $10,712 per year. Even with two minimum-wage earners in a household, it would be tough to get by.

Jacobe: Yes. That's why, in a sense, the minimum wage isn't really an issue, because even a substantial increase in the minimum wage will not bring it up to a level where it will have a significant impact on wages. Many other things have happened to low- and middle-income earners' wages that have made the minimum wage irrelevant.

GMJ: Like what?

Jacobe: A lot of the jobs that used to be minimum wage jobs have gone overseas, been offshored, so there isn't demand here for them. Some of these jobs have been taken by illegal immigrants who have little bargaining power and sometimes aren't even paid the minimum wage. And most businesses in America are already paying more than the minimum wage -- they have to, to attract workers. So there are very few minimum wage jobs at all in America.

Now, two things used to be key aspects of the minimum wage. The first was the notion that the minimum wage was how small businesses brought people into the work force. The second was the idea that for big employers who had a lot of minimum wage employees, when the minimum wage was increased, it pushed up wages throughout the company.

GMJ: And then the company goes under because it can't meet the payroll. Is that what really happens?

Jacobe: Most large companies today are paying above the minimum wage for the simple reason that people won't work for money they just can't live on. All these downward pressures on the lowest paying menial jobs have taken them out of the structure, and businesses are willing to pay higher levels of wages for the jobs that are left. Now, there are still some people who are subjected to the minimum wage, and even though it's a relatively small group, it's psychologically a big issue.

GMJ: According to several lobbying groups, like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a minimum wage hike will hurt the backbone of the economy.

Jacobe: Well, in an economic analysis, there is no real justification for the minimum wage. In fact, it inhibits the free market. In that kind of analysis, there are always companies on the margin paying the minimum wage, and some of those will go out of business if their labor costs increase. My guess is that there are few such companies left. Most of these companies have probably already replaced their minimum wage employees, or will do so soon, by going to one of the other two sources of cheap labor -- job outsourcing overseas or hiring illegal immigrants who don't have any choice in the wages and benefits they earn.

So if that's true, then based on the results of our most recent survey of small-business owners, the Wells Fargo/优蜜传媒Small Business Index, the real economic effect ought to be basically minimal, if there's any at all. So, the real cost of a reasonable increase of minimum wage probably is not significant because U.S. minimum wage laws have effectively been undercut by the global labor market and illegal immigration. Now, you can argue that if you keep increasing it really rapidly over a period of time, that at some point it will become binding.

GMJ: But don't some companies use the minimum wage as a baseline, even if they're paying well above it? So if the minimum wage is bumped up $2.10 an hour, won't they have to increase wages by that much to stay competitive?

Jacobe: Well, not necessarily. If they're paying considerably over the minimum wage at the current time, it doesn't really affect them directly. You might think that increasing the minimum wage will cause wage-push inflation, but the results of our recent survey suggest that small-businesses owners, in large part, don't pay the minimum anyway.

In essence, I think the small-business model has changed significantly. In the past, many small businesses did use minimum wage labor. Today, however, most small businesses aren't really competing for low skilled labor in the global markets or by using illegal immigrants. Instead, they are competing for highly skilled labor in the United States and are having a hard time doing so effectively.

|

The survey results are interesting because philosophically, most small-business people are economically independent. They tend to believe strongly in the free market and therefore would oppose the minimum wage. But, as we found, it doesn't affect them.

GMJ: Do you think that a minimum wage is part of a strong economy?

Jacobe: I don't think so. I don't think you can argue that. But there's another argument to be made, a social one, that says people need a living wage, a wage that the average American can reasonably be expected to survive on. And so to the same degree that we set Social Security payments, society makes certain judgments about those kinds of issues. What we try to do is create stability in the U.S. labor markets by establishing reasonable "rules of the game" for the free market. The basic argument is that the labor market is not really "free" in the pure sense due to the concentration of economic power in the form of oligopolies and monopolies, and that wages, benefits, and working conditions are all strongly affected by economic concentration. As a result, government has to step in and set minimums that are acceptable to society, such as child labor laws, environmental laws, and yes, the minimum wage. What's happening right now is that many multinational corporations are circumventing these U.S. rules by shopping for cheap labor on a global basis and/or by using illegal immigrants in the United States.

In free, unfettered capitalism, you often get high degrees of economic concentration and government corruption that results in the kind of effects you see in the Third World. You get a bunch of workers who are paid nothing, while those who own capital and corporations and so forth garner all the wealth, which creates a huge inequity in income.

GMJ: That doesn't make for a very stable society.

Jacobe: No. And that's why we have instability in so many parts of the world.

GMJ: Isn't that why the U.S. government has put so many controls on U.S. businesses -- laws and regulations -- one of which is the minimum wage?

Jacobe: That's exactly right, but finding the right balance between a "free" competitive economy and establishing the optimal "rules of the game" is a huge challenge for every economy. In this regard, I think the big danger for the United States in the future is the political economy. The failure of government to address the minimum wage may be seen by many middle- and lower-income voters as a symbol that their current representatives are out of touch with the wage pressures today's employees are feeling from the global labor market and illegal immigration. In turn, this could lead to a change in political representation that is both protectionist and proregulation. The result could be the passage of laws and regulations that make the United States much less competitive in the global economy -- an outcome that is much worse than an increase in the minimum wage.

GMJ: You've mentioned offshoring several times. Does having a national minimum wage directly encourage job offshoring?

Jacobe: Probably. Probably. There's an example down in North Carolina where I live. Recently, Continental Tire in Charlotte told its workers, we're either going to shut down this plant, or you have to agree to lower wages, because labor is so much cheaper offshore, and we can't afford to pay the kind of union wages we do here. Now, they have decided to move virtually all their production overseas. Well in theory, the same thing applies to every U.S. business.

So job offshoring clearly drives down wages in the United States; it's definitely a substitute for U.S. labor. And again, an economist would argue that's an efficient free market the consumers benefit from, and if it's cheaper for business to produce stuff in some other country, then that's fine. But that view only looks at the global economy and doesn't take into account social effects, social considerations. The fact is that job outsourcing overseas undercuts U.S. minimum wage laws.

GMJ: So what's the connection between the minimum wage and illegal immigration?

Jacobe: Well, when you set the minimum wage, employers can go out and get anybody to work for them at that level. And so in a competitive context, every company bears the same cost. Therefore, they would have to pass it on to consumers. But if employers can hire a worker who is not subject to U.S. legalities and is willing to accept pay under the table, they can cut costs significantly. There are a variety of companies that have done that. And even if those companies aren't paying minimum, it's likely still more than the illegal immigrants would have made back home, so while illegal immigrants are "exploited" in one sense, they will continue to come to the United States. Again, in essence, illegal immigration simply circumvents U.S. minimum wage laws.

GMJ: You mentioned that increasing the minimum wage isn't small businesses' primary problem -- it's finding skilled workers.

Jacobe: Well, the problem for small companies is that they don't get the economies of scale that large companies do, so they aren't able to provide as many benefits, like health insurance or 401(k) programs. The other big thing that they can't provide is opportunities for advancement, so it's hard for workers to see a career path. It's not just a matter of money, it's a matter of all the other things that they can or cannot provide. I think a real avenue for small businesses to attract labor would be to give their employees a share of ownership. Giving employees a stake in the company can make a big difference.

GMJ: What has technology done for small businesses that a minimum wage hike can't?

Jacobe: More and more small businesses are using technology like computers, cell phones, and PDAs, and they're able to increase their per-person productivity -- do things a lot more efficiently -- because of the technological advances. Just being able to respond to e-mail or be available on a cell phone is a big advantage for a small-business owner -- he doesn't have to hire someone to be available because he always is.

Then there are computer programs -- people used to spend hours and hours doing things they're no good at, but now basic computer programs can take care of that fairly simply. All of those things save the small-business owner a lot of time and money. Business owners have to be jacks-of-all-trades; they have to do their own accounts, their own taxes, tracking, ordering, billing. So as they've taken advantage of technology, they have had to hire fewer people to do some of these basic business functions. They don't have as much pricing power on the sales side as they have cost pressure, but they've been able to offset that with increased productivity via technology.

But they can't sort of multiply themselves effectively in certain high-skilled areas. They can't do everything. That's where they're having problems. Not because of the minimum wage.

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison