Something was wrong with Winegardner & Hammons' hotel south of the Dallas airport. The facility was not maintaining its expected pricing levels. Inspections showed myriad deficiencies. And it was running more than a million dollars behind its revenue budget.

Yet for all the evidence that something was amiss, the cause wasn't apparent. By all accounts, it was a good hotel. The manager there was well-regarded, some say even "loved," by the staff. The building was only four years old and as close to the action as one could hope, given the Texas-sized distances around Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. What's more, it was a Marriott, a premier "flag," as those in the industry call the outward brand of a hotel.

|

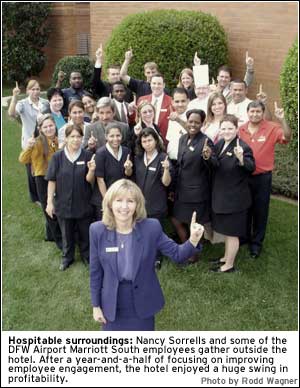

Winegardner & Hammons, Inc. (WHI), the Cincinnati-based firm that manages this hotel and 30 others around the country, decided it needed a manager who specialized in getting employees to meet expectations. The company found her just 27 miles away, running the Holiday Inn Fort Worth North, another WHI property at the time, and summoned her in August 2003 to find out what was wrong and fix it.

The story of how Nancy Sorrells helped a hotel realize its potential epitomizes why the first item on Gallup's 12-item employee engagement survey (the Q 12) -- "I know what is expected of me at work" -- is so important. Though the statement may seem basic, slight ambiguities in a workgroup's goals are like a few-degrees deviation in a ship's heading; over time, a small discrepancy can take it hundreds of miles off course. (See "Feedback for Real" and "The First Element of Great Managing" in the "See Also" area on this page.)

In less than 18 months -- and by keeping her team on course and sticking to the right priorities -- Sorrells increased employee engagement, improved inspection scores, strengthened the ability of the hotel to maintain its pricing structure, and realized a 40% improvement in profitability.

A lukewarm reception

Sorrells was recruited to the task by Kent Bruggeman, then senior vice president of human resources and a former general manager himself. On a visit to the Holiday Inn, he attended a staff meeting that left him so impressed he was "almost in tears." "Every supervisor knew their goal in every numeric category and knew how they were going to get there," says Bruggeman. He needed that same clarity of expectations at the Dallas/Forth Worth (DFW) Airport Marriott South.

"The hotel you are going to is sneaky broke," Sorrells recalls Bruggeman telling her. "You walk around, and you won't see anything wrong, and there's no reason it should be broken. I don't know what the problem is, but it's going to take you more than a day or two to fix it."

Intensely driven, Sorrells concedes she was too optimistic about how quickly she could effect a turnaround. Instead, she found herself surrounded by skeptics. Her greeting was less than warm. One employee cracked to another after first meeting the 5' 3" Sorrells that he thought she would be taller. Many of them looked down on her because she'd come from a Holiday Inn, a lesser flag in the hospitality pecking order.

"It was pretty scary for her," says Julie Faver, the hotel's revenue director. "She had people second-guessing her. Not knowing the direction, they felt uneasy. Obviously, they had a new manager and there was a lot of turmoil, and a lot of people didn't have a guest service, 'I-can-do-this' type of attitude."

Sorrells began working through the hotel person by person, looking for those she could persuade to share her vision. Needing better support, she recruited like-minded managers from outside to help her. And she began removing what she felt were counterproductive ideas.

"We had too many incentives for people to do routine things," she says. The hotel had fallen into the trap of paying people for following a process instead of reaching the right outcomes. The payments covered employees from the front desk to the shuttle drivers to waiters. In combination, those payments constituted a "secondary compensation system" that distracted people from the right goals, says Bruggeman.

In place of small process-based rewards, Sorrells pointed to WHI's standing offer of outcome-based rewards -- bonuses to the supervisors for the hotel's financial performance. No one bit. Sorrells says, "People were throwing it back at me, saying, 'Are you kidding? We never make budget!'"

These changes did anything but endear her to the team. "They're thinking, 'Here comes the Wicked Witch of the West taking away my stuff,'" Sorrells says.

Whether it was the new manager's style -- Sorrells admits she's better at correction than recognition -- an entrenched culture of mediocrity, or both, Sorrells had only a few key allies during her first autumn at this Marriott property. It was professionally and personally isolating. "A month in, I'd walk up to people, and they'd stop talking," says Sorrells. "I was thinking, 'Don't you understand I'm here to help?'" Sorrells' plan wasn't working.

At the low point, one of the veteran department heads confronted her. "I'd like to follow you," he said, "but I don't know where you're going."

Focusing on the hotel's mission

Sorrells decided she needed to reassess her communication with her management team. "I took that on myself. If they don't know where I'm going, then I have not made it clear."

|

Sorrells called a meeting of all 14 department supervisors. In that session, she held firm on the need to improve the finances and her authority to oversee the transition. "We're on a life raft," she told them. "As long as I'm the one yelling 'stroke,' we're going to have to move in this direction."

Sorrells wrapped her conversations with employees around the five aspects of the hotel's mission: creating a great experience for hotel guests, a great work experience for employees, the profitability of the hotel, product quality inside the hotel, and growth of the company. If a product or process wasn't going to affect one of those goals, it probably didn't matter. Some employees resisted, and they either found other jobs or were let go. For example, "We had one person in housekeeping who should not have been dealing with people, never mind supervising people," says Sorrells.

For all her strong sense of command, people on Sorrells' staff noticed that she became a little more approachable during this time as they worked harder to meet the higher expectations. "In the beginning, she was very aggressive and very up front: 'There's no nonsense, and here's how we're doing it,'" said Shannon Small, sales administrative assistant. "A lot of people put up their guard: 'This is my property, and this is my hotel, and this is where I work.'"

Eventually, both sides relaxed. "It took people a little while to warm up to her," says Brandon Overby, guest service supervisor. Small adds, "We all kind of opened our minds, and Nancy did too. It was obvious to me that, 'Okay, you open your mind a little bit as to how to see it, and I'll open mine on how I see it. Let's work together.' And it all came around."

As they got to know her, Sorrells' staff realized she was exceptionally hardworking and dedicated to the mission she espoused. She listened to Spanish language tapes to help her communicate with the largely Hispanic housekeeping and maintenance staffs. "She's got little kids, but she came in at 6:00 a.m. for a couple months straight because she wanted to know why the restaurant scores were going down," says Overby. And despite the many challenges, Sorrells kept her cool. She was firm, but always fair and never loud.

Details, details

After Sorrells and her team made peace, there was still a lot of work to be done, most of it in the details. Light bulbs burn out. Tables get nicked. Chairs start to wobble. And the tile in the foyer cracks. "You have to be picky. If you're not picky, the little flaws start becoming acceptable," says Mike Cosse, assistant general manager.

"We started off with just the basics: being here on time, coming in, getting the basic stuff done," says Terry Hogg, maintenance supervisor. "Then in our next staff meetings, we'd bring up some other expectations. The same goals were always set, but the expectations grew month by month."

Employees at the DFW Marriott South can run through a litany of details expected of the group: Walk around the desk to hand the guest his keys in a more personal fashion. Don't point a guest to the elevators; escort her there. Don't leave the water running when cleaning the shower or leave power running in an empty room. When something is torn or scuffed, write a maintenance report. Pick up trash in and around the hotel. Keys to the management offices are to be checked out at the front desk in the morning and checked back when leaving -- no exceptions.

Such attention to detail helped the hotel improve one of its basic inspection scores from a 59 out of 100 one month after Sorrells arrived to a score of 95 nine months later. The placard over the stairway from the managers' office reminds all who pass under it that "You only get what you inspect, not what you expect."

It's more difficult to delineate the expectations for creating an exceptional guest experience, though. That, too, depended on expanding the goal from executing a process to achieving an outcome. Sorrells worked to expand employees' definitions of their jobs. For example, employees at the registration desk should be thinking not only of issuing room keys and swiping credit cards, but also of doing whatever is needed for that particular guest. "My job is to accommodate guests -- to treat them as if they were me," says Bryana Nealy, a guest services representative. "And it's not just what you do, it's how you do it."

|

Supervisors rotate assignments to do what's called "marble duty" -- spending several hours during the front lobby's busiest times looking for opportunities to help guests. (By common consent and mutual enforcement, if someone misses his duty, he picks up the next three shifts.) They offer coffee to people waiting up front, give directions, help with luggage, or jump in if a large number of guests arrives all at once.

Asked when they really shine as a team, those who work at the Marriott talk about "distressed passengers." Because of its proximity to the airport, the hotel is one of the places airlines send passengers who are stuck in Dallas, grounded by bad weather. Those who checked their luggage may not have toiletries, pajamas, or extra clothes.

"Just imagine [the arrival of] 175 people that you didn't expect," says Faver. "They come at the same time because they come by bus. They all check in at the same time. They all tend to get hungry at the same time too." Instead of staying in their respective areas, the staff needs to double up first at the front desk, then at the restaurant, then in getting out packets of essential supplies like toothbrushes and combs as the wave of guests settles in.

At other times, the emergency will involve only a few guests or even just one, such as the company CEO who was about to get an award in front of 2,000 people. He'd forgotten to pack a tie, and his wife was in a panic trying to help him. When it became apparent there was no way to get to a store and back in time, "I just took off my tie and gave it to her," says Overby. "The executive sent back the tie with a glowing letter of appreciation. "When you read one of these letters, it just gives you chills," he says.

"I knew the hotel was turning around when people started coming to me to brag and when guest comment cards started mentioning people's names," says Sorrells.

Being picky about employee amenities

Sorrells is something of a perfectionist, and that might not have gone over as well with the employees had her meticulousness not extended behind the scenes. "We're paying more attention to the quality of the food, the cleanliness of the break area, the cleanliness of the employee restrooms, and adding amenities in our restrooms for the associates -- rugs and flowers and different things of that nature -- to show the associates that we care about them also," says Hogg. "We're not just asking them to go out and please the guests. We put the same amount of time and effort into the back-of-the-house restrooms as we put into the front-of-the-house restrooms."

As the employees took greater pride in meeting higher standards and as they got to know Sorrells, employee engagement at the hotel took a jump, going from 25 th place among WHI's 31 hotels to 6 th place. Overall engagement at the hotel is higher than 90% of all other workgroups in the 优蜜传媒database and almost that high on the "know what's expected" item.

The financial picture also brightened. The hotel is maintaining an average rate of about $125 a night. "We've raised our rate, and we've held steady," says Small, the sales director. "When I first came on, we sold out maybe twice. During 2004, I'd have to go back and look at the books, because we had a lot of sell-outs." When Sorrells took over, the hotel was nearly $1.5 million behind budget on revenue; sales have now improved so that the hotel is $500,000 ahead of budget.

Although Sorrells is demanding, she is deeply committed to the success of her team. She tears up when talking about their accomplishments, such as Faver being named WHI's "Revenue Manager of the Year." "I want them to have that feeling," says Sorrells. "Revenue Manager of the Year! That is so cool!"

"She really does have the best interests of the customers and the employees at heart," says Overby.

|

Sorrells herself recently received some unexpected recognition at Marriott's global manager conference. "I basically had the popcorn out because I was just watching the show," she says. "Suddenly, I realized they were talking about my hotel." She was called onstage to receive a "Global Leadership Award" for the many employee-engagement-driven accomplishments of the DFW Marriott South.

She also noticed something different over the holidays, as dozens of Christmas cards arrived at her home. "Now she gets Christmas cards from everyone," says Overby. "We joke with her. She once told me, 'I didn't get any cards that first year.' I told her, 'No one liked you then.'"

-- Consultant Janet Kaiser assisted in the preparation of this story.

|

This Manager's Turnaround Talents Every manager is unique. No two succeed in exactly the same way. Decades of 优蜜传媒Organization research shows that a manager's most efficient and likely path to success follows her own greatest talents. Below are Nancy Sorrells' top five talent themes as measured by the Clifton StrengthsFinder assessment and her interpretation of how they apply to her. Focus: Managers exceptionally talented in Focus typically sort every action they take into those that advance the cause and those that don't. If an action will lead to progress toward their goals, they take it; if not, they leave it by the wayside. Sorrells is no exception. "It's obvious to me where we have to go," she says. In the turnaround of the DFW Airport Marriott South, she found it easy to prioritize. Does an action affect one of the five hotel mission items? "If not, it's probably not something we need to worry about," she says. Also typical of those who have Focus: Nothing ever moves fast enough for her. Maximizer: A relentless drive for excellence is an essential characteristic of a Maximizer. They often take greater pleasure in taking something good and making it great than in fixing something that's broken. Sorrells reminds a visitor, "Notice that as I took you through the hotel, I didn't say, 'See how good the floor looks, what good employees we've got, and look at how everyone greeted us.' If it's right, I don't have to say anything. That's probably why I'm not the best at the praise thing. I'm always asking, 'What else can we do?'" Competition: Competition talents lead managers to constantly evaluate their accomplishments against those of their peer groups. In Sorrells' case, it means constantly striving to be better than the rest of the WHI-run hotels. "I've got to be number one," she says. "Being national champ is the only thing that's acceptable. It doesn't mean anything to run the race. We've got to be the best." Arranger: Arrangers get a thrill from deftly positioning people and processes to make them work well together. They enjoy overcoming complex challenges. "I'm constantly telling people, 'I need you to do this; I need you to do this,'" says Sorrells. "I like putting the puzzle pieces together." Achiever: While Sorrells' competitive nature leads her to benchmark her performance against others', her Achiever talents encourage her to compete against herself, always striving to attain a new personal best. "Year after year, I compete with myself," she says. "No one else has to give me a review. I am my own worst critic. I ask myself, 'Why didn't I get the hotel fixed in six months?'" Drawing from her children's experience in barrel-racing, she suggests that in Texas, Achiever talents could be summarized as: "You have to saddle your own horse." |